Photos: Etty Fidele and (insert) KOBU Agency, on Unsplash

This webpage is for trust fundraisers with three or more years’ experience. Beginners should use this page instead.

Photos: Etty Fidele and (insert) KOBU Agency, on Unsplash

This webpage is for trust fundraisers with three or more years’ experience. Beginners should use this page instead.

In a strong proposal, it’s clear that everything’s eligible, you’re doing work (preferably “clearly good” work) that will clearly deliver clearly significant benefits to people who are clearly in need. Trusts will read between the lines and make assumptions about your work. Even if as an assessor you can somehow avoid that beforehand, reading between lines becomes inevitable when you’re down to separating the borderline candidates. At some point, you start grasping for reasons to reject otherwise strong bids.

A second issue regarding clear proposals is that a common reason trusts give for rejecting proposals is “lack of clarity”. That term can mean a lack of definition in the project or internal contradictions. Sometimes it can be a euphemism for “We aren’t convinced you know what you’re doing”. However, it can also be because the proposal is confusingly written.

In my experience assessing, it’s harder to give someone a grant if the proposal is confusing. It’s also annoying to try and fathom out what’s going on – which is not a great start.

When I’ve critiqued other people’s proposals, the lack of clear writing is often due to a poor underlying structure to the writing itself. If the proposal is a mess, redoing the structure and then rewriting will often cure this. The longer and the more multifaceted the application becomes, the more essential a strong structure is. Also, the more interrelated facets of the proposal there are, the harder you will need to think about the structure before you start writing.

Conversely, behavioural economics says the familiar “lands” better and a lot of powerful arguments have a common-sense quality to them. You only get that by thinking hard about the kernel of your argument and bringing it through clearly.

As professor of behavioural science Robert Cialdini says, using an intelligent but uninformed outsider to review your proposal will do a lot more for clarity than relying on re-reading it yourself. Every book advises this, I never see people do it… But my experience is it does work. They don’t have to see a polished draft with no gaps, they’re not approving your work.

There’s a case for making your application memorable. When I watch grants panels discussing applications, they clearly have to remember what you have said. Some of that is about making your writing clear and un-confusing – but there is more.

There is a school of thought that text which requires a little effort physically to read, or that is slightly uncomfortable to read, is notably less memorable. This is because the distraction of trying to physically reading it impairs the reader’s ability to remembering it.

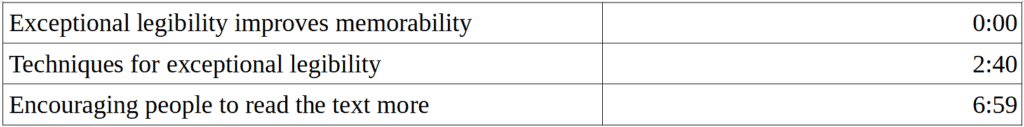

This brings in issues like: the typeface, the layout of your text, ink colours. Much of the research was done by Colin Wheildon, who asked groups of a hundred or more people to read A4 pages of text that were written in different ways and compared how much they could remember. The following presentation illustrates many key points. However, the following is a quick summary. The points apply to the “body text” (rather than the headings, etc) unless otherwise indicated.

When I discuss how to increase legibility with trust fundraisers, they say the same as many of Colin Wheildon’s audience: that impactful design is also important in conveying the message. It is easy to apply the above rules and produce a more boring design. As a fundraiser you will need to seriously consider the overall impression you make. However, I would say that, if you do not also bear in mind what will be remembered, that’s a mistake.

Wheildon, Colin (1995). Type and Layout: How Typography and Design Can Get your Message Across – Or Get in the Way. Berkeley: Strathmoor Press

or Wheildon, Colin (2005). Type and Layout: Communicating or Just Making Pretty Shapes? Worsley Press Australia covers the same ground, but slightly expands on it. Hopefully this web site gives you everything you need, but the book might give more clarity and background.

In the 90s there used to be surveys of why trusts reject you and one common reason given for rejecting proposals was “lack of clarity”. You’ll still hear that from individual trusts when they present.

In my experience assessing, it’s hard to give someone a grant if it’s confusing what they’re actually asking for. It’s also annoying to try and fathom out what’s going on – which is not a great start.

One point that immediately occurs to many people here are: if it’s jargonistic. It’s easy when you’re part of an organisation for a while to fall into the common language and assumptions of that group. One of your roles is as translator, you need to leave all that behind. A good style treats the reader as a lay person without specialist knowledge, but the content still works well if they actually know a lot more about the subject.

A second point is if it’s confusingly written. One example: as an interviewer, I’ve rejected a fair number of people with postgraduate degrees in the arts. The demands of postgraduate writing can make people’s prose so convoluted that it’s too difficult to read – however precise it may be in other ways.

However, the big one is really a lack of good structure. When I’ve critiqued other people’s proposals, the lack of written clarity is often due to a poor underlying structure to the writing itself. If the proposal is a mess, redoing the structure and then rewriting will often cure this. The longer and the more multifaceted the application becomes, the more essential a strong structure is. Also, the more interrelated facets of the proposal there are, the more you will need to think hard about a workable structure before you start writing. If you’re co-authoring long, complicated bid, it gets even worse.

You need to show basically how much of what is going on. It needn’t be precise, but if the description could cover a number of quite different versions of the same project, the funder doesn’t know what they’re being asked to assess.

I think there’s a real difference in this regard between “gift givers” (people making an intuitive, probably quite quick, decision about what appealing work to fund) and “grant makers” (people thinking strategically and more thoroughly about how to make the greatest difference with the money available, by evaluating proposals to identify the greatest impact – see the Classifications of trusts webpage regarding this distinction). I was at a charity with lots of gift givers of all sizes in their portfolio and the descriptions of services had a higher level of ambiguity. However, they had a good success rate amongst their gift givers.

I think clarity is sometimes used as a synonym for “We’re not convinced”. Convincing funders is covered in a lot of other sections in this website. However, there’s a distinctive point that can be made, here.

When you’re deciding which of two more borderline projects to pick, there comes a point where, as a selector, you can start grasping at straws a little bit. Are these clients REALLY eligible? Is that clear? Are they REALLY in need? Are they REALLY better off? Does the project REALLY get them there?

As a writer, you want to have that clear, undeniable throughline of eligible service users and work. Your application may not be perfect in all the details, but if those central points are clear and undeniable, you’re protected against that particular form of rejection.

As behavioural economics says, the familiar “lands” better and a lot of powerful arguments have a common-sense quality to them. You only get that by thinking hard about the kernel of your argument and bringing it through clearly.

As professor of behavioural science Robert Cialdini says, using an intelligent but uninformed outsider to review your proposal will do a lot more for clarity than relying on re-reading it yourself. You also need to be careful if they misunderstand your work and criticise it on that basis. If the reader has made that mistake, could others do the same? Every book advises you to get others to read things, I never see people do it… But my experience is it works. (I occasionally use my parents!) They don’t have to see a polished draft with no gaps, they’re not approving your work.