Photos: Chokniti Khongchum and (insert) Fauxels on Pexels

This area of the site was written for very experienced trust fundraisers.

Photos: Chokniti Khongchum and (insert) Fauxels on Pexels

This area of the site was written for very experienced trust fundraisers.

There’s lots of good generic advice about starting a new job. I recommend you look at some of that, too

Firstly, you need to make a lot of time at the start for learning. You’ll come in with some good, solid skills, but the context in which you’ll apply them may be extremely different. It’s tempting to want to plunge into fundraising as soon as possible, but a major initial task is to learn what’s actually going on, in very many different senses.

Secondly, manage your expectations of yourself. Suddenly, you know a lot less than you did, you’re learning new skills and you need to be realistic about the time it takes to get up to speed. At my current charity, we have half a dozen services and a fairly subtle, complicated trust fundraising programme. We had a fairly experienced trust fundraiser come in who was new to our work and had a little bit of skills development to do. By the end of six months, she knew many but not all of the services and was working to speed. That reminded me very much of my earlier career. (Getting up to speed does get much faster.)

Your approach to this will be very different if you’re coming in to cover a vacant post for a few months, say (when it’s reasonable to ask to be spoon fed more) or you’re putting down roots for a couple of years or more.

If you’ve only worked in one or two places, you’ll still be well aware of many differences you need to be you’re inducted on:

However, there’s a lot more that might not be so obvious:

How you will work and get things done will vary greatly, depending on the type of charity. Henry Mintzberg has quite a helpful framework for appreciating the scale of difference:

There’s a simple, flat structure with one or a few top managers. It’s relatively unstructured and informal, with a lack of standardized systems that allows the organization to be flexible.

If you’ve come from a charity like this, you may wonder what on Earth is the point of all the pages about trying to get Services to work with you. At the same time, you may have lower expectations about quality of data.

If you’ve worked at a care charity, you’ll recognize this. The charity is defined by its standardization, the work is very formalized, there are many routines and procedures, decision-making is centralized, and tasks are grouped by functional departments. You won’t get anywhere without good senior buy-in.

Although there’s still plenty of bureaucracy, rules and procedures, there are lots of highly trained professionals. So, decision making is decentralized. Think: schools and universities, or to a lesser degree, addiction charities. It’s hard to create change, as there are both lots of rules but also staff have more autonomy.

This is the common structure of large nationals. A central headquarters supports a number of autonomous divisions that make their own decisions and have their own unique structures. If you sit in the office expecting the work to come to you, you’ll probably fail.

The central team can focus on “big picture” strategic plans, so you need to involve them. However, they only have limited control over Services, which can be pretty “siloed”. So, you need all your influencing skills and political antennae to make everything work well. If your manager has come from a background managing a corporate team in a smaller charity, for example, they may barely appreciate what you have to do for a living.

If you’ve worked in an umbrella organisation with a strong development function, you may recognize this. Where services need to innovate and function on an “ad hoc” basis, bureaucracy, complexity, and centralization are far too limiting.

Decisions are decentralized, and power is delegated to wherever it’s needed. As such, there’s less central control, more conflict and you may find relations with functions can vary and even be a bit of a headache. However, if you can make things work, they’re great fun.

Managers don’t necessarily share your priorities. You want to pass your probation and if you want to thrive, you’ll benefit from their backing. So, find out early on what’s most important to them – and if you can’t succeed with anything else, at least get those one or two things right. If they say something that’s not fully within your control, such as “meet your target” then you’ll at least know that and you have time to influence them appropriately.

Your donor records are a great starting point. Try and get printouts of

They will tell you:

You might quite reasonably think it overkill to ask your future boss to get services to identify an introductory book to read before you start. However, it does help.

My starting point for understanding the services is to read proposals that describe the services in a little depth, then watch some “a day in the life” videos of service users in my new field of work.

If I need more for some reason (e.g., I’m doing a few massive applications) it can help to look for:

Something else to work out quickly is: how to find all the names and roles? I look for organograms, diagrams with faces and names, departmental lists. Worst case scenarios: you can sometimes find staff job titles in the list of names on Outlook, or you can spend half an hour researching your charity’s staff on LinkedIn.

Yes, you need to make a good impression. However, when I’ve seen trust fundraisers try and impress Services with their knowledge of the work in induction, it’s looked silly. However, you can impress people at this stage by:

Questions are one of your core skills and your stock in trade. People who’ve done things for you are better disposed towards you. So as long as you’re not asking questions to the extent you’re imposing, it’s a good way to get going.

At this early stage, you’re looking for mentors/”older siblings”, especially within Services (but also for things like IT, the database and the phone system) who you can turn to in future. Asking lots of questions will help you see who can fill that role.

My experience is that my own manager has rarely wanted to hand-hold my work and anyway, they wouldn’t be able to apart from team/Departmental systems. You therefore want to create your own support network, for when you need help.

I’ve always felt that one of my few real superpowers was that I’m not embarrassed to ask questions, including of: my predecessor in the role, people who don’t know me from a hole in the ground; or people who haven’t seen me for a decade. Asking questions is getting the job off on the right foot.

Giving and getting back because there’s a partnership (not in a “tit for tat” way, but in an “it’s what partners do” way) is a good influencing approach. (See under Persuasive Communication under Working with Services.) As you start to identify your key partners, you can start doing/offering to do small, easy things for them spontaneously. It’s putting the relationship on a positive footing and subtly invites them to start behaving like partners, too.

When you’re on the phone to funders, it can help if you’ve seen the work in action. It helps you in overcoming misconceptions about what the Services actually do. 18 months from now, when you’re getting bored doing the same things over again for the same projects, you’ll be grateful for engaging with the work on the front line, because you’ll care more about it. It’s also one way to collect some stories to share with funders and to build soe rapport with the cause.

Everyone goes through a period where they can’t really, fully, properly do what they’re expected to. There’s nothing wrong with plunging in and having a go. If it doesn’t work – what do people expect? As long as you’re honest with your manager, you’re covered.

People, including Services and your manager, will be forming opinions about you. Quick wins can help early opinions form positively. Also, the chances are that, come the end of your probation, there won’t be that much positive feedback from funders. However, if you can get some going, that helps create a good impression. It’s good for confidence, too. I’ve sometimes asked my manager (or my predecessor) if they can spot any quick wins. Depending on how they’ve been picked over by your predecessor, lapsed donors can be a quicker win.

That means Services, plus maybe your manager. Despite being in the Fundraising Department, Fundraising aren’t often really your actual colleagues. They’re just sort of around. If you get the chance to get to know your Services colleagues as people, it will stand you in good stead. Services managers tend to be good company – they usually have good people skills and you’ve got shared interests.

You’ll possibly always be a bit of an outsider with Services (which is a good thing, in some ways). However, you can get a good way if you go to the very occasional team meeting, chat as well as just doing business, speak to them and not just Fundraising at charity-wide get togethers, try and have sandwiches with key contacts occasionally and try to go to the odd Services awayday.

As my editor, Robyn McAllister, pointed out, Services aren’t always based in the same office, but these days there can be virtual socials that can help.

Other good people to know a bit:

If this all sounds like just for extroverts: I’ve spent periods of three to six months on solitary retreat and rarely see anyone at weekends. I get to know people socially because it works. The fact they’re inspiring, interesting individuals is a bonus.

You very likely cannot work at the same speed in your first six months as you will later in your job. Your target was probably set for your predecessor, who was up to speed and you may well be watching it disappear over the horizon as you struggle to speed up (never mind that your post has probably been basically vacant for some months with a minimum of relevant applications going out). That’s not your fault and as it’s out of your control you’ll have to take it on the chin.

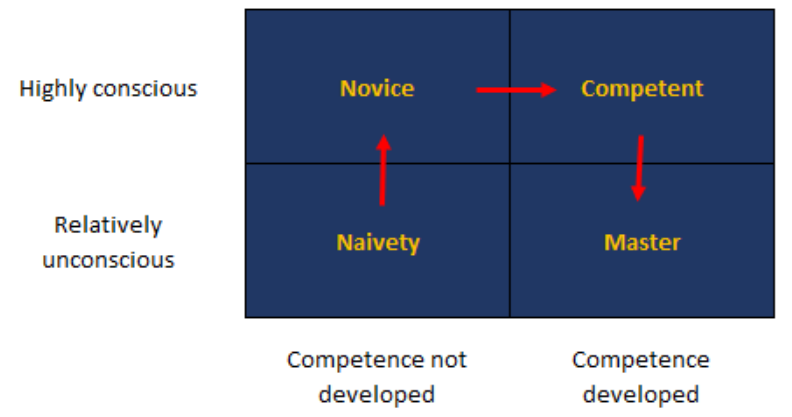

If you find yourself a few months or more into the role, facing a dip, personally – that’s normal, too. The excitement has probably worn off and the realities of not being good enough (yet) are fully in play. If you have the illusion that you really aren’t good enough because you’re too slow, at this stage I’d question it. The way people develop doesn’t fit very well with their conscious sense of how they’re getting on:

When people start in a job, after the initial worry beforehand and maybe stresses around whether it’s as advertised, it’s a happy time. Then, you really realize the tasks in front of you. That can be interesting, because you feel stretched, but equally it can be stressful because you can do the work, but just not as quickly as you think you should be able to. However, it’s only when you get to what I’ve labelled “mastery” – being competent but doing things as second nature, without thinking that much – that you’re probably flying along.

There’s too much to learn to do that. It tends to be a one-off opportunity. After that, the year before’s Key Performance Indicators and targets kick in and you may find you’re too busy to do lots of induction-type learning.

Hopefully everything above has convinced you of this. Having skills doesn’t mean doing the same things. Large and small charities for example, are hugely different. Likewise newly created roles and existing ones.

When you start out, you don’t know what you’re getting into. For that reason, it may be better to avoid making too many promises. I’ve had the odd job where I’d oversold myself slightly at interview and it was an uncomfortable start for me to the work. (Not a situation I’d recommend to anyone.) Looking back, it might have helped to mention a bit more early in the job the things I didn’t know yet, but needed to, in order to deliver.

Again, you can see how important all the differences are in this context. The old adage can apply about the seeds of failure being contained in your past successes. One of the more fun things about a new job is seeing which of your past successful approaches work in the new context and how they adapt.

This means: focussing too much on senior staff and anyone you’re managing.

It’s worth Googling about starting a new job – there’s some generic advice that’s sensible. A lot is very basic and about Week One, rather than how you really get into the role.

The best book I’ve come across for starting a new job is The First 90 Days by Michael Watkins. It’s pitched at executives, rather than people like us, but it’s got some great content (that I’ve borrowed liberally from for the lists, here).

Episode 76, The calling of Public Service, of the Doing More Good Podcast covers starting a new job. It’s not amazing, but it’s fun and at least about FR in some sense.