Photos: Cliff Booth and (insert) Christina Morillo, on Pexels

This webpage is for trust fundraisers with three or more years’ experience. Beginners should use this page instead.

Photos: Cliff Booth and (insert) Christina Morillo, on Pexels

This webpage is for trust fundraisers with three or more years’ experience. Beginners should use this page instead.

If a project is important and complicated, I always aim to have a grant induction meeting with Services. This is usually with the Services manager, though if the changes involved require understanding across the team, a wider meeting might be needed. (I showed this to Robyn McAllister of Street League, who commented that she usually involved Finance as well, if it was a restricted grant. That sounds like a good idea for some contexts.)

An induction meeting covers:

I’ve been at charities where we’ve had full access to all monitoring data, there have been absolutely no problems with this and it’s been convenient for Services. If need be, the Trusts team can be DBS checked.

You may not want that level of involvement, though. It avoids a log jam sometimes in terms of Services not complying. However, there can be issues understanding the system / getting clean data, that you may prefer to leave with Services who’re doing it for other purposes.

One advantage with access to the data is that it enables you to slice up the work many different ways, broadening the ways that you can fund the work.

At my current charity, there are services I meet monthly on behalf of my team to keep on top of all the nuances. (Services where I am just now are very helpful indeed.) At other charities I’ve met quarterly and sometimes you can trust people to leave them until the reporting process, bar the odd quick check-in call. Considerations include:

For services we work closely with and where we need to pick up even small changes, I meet them monthly and use the following template:

Trusts (at least, the big ones) are well aware that changes are a normal, natural part of a project. I’m writing this (hopefully) after the worst of the pandemic has finished and at this stage, trusts seem pretty receptive to the reality of projects changing. However some changes can be very substantial, in which case there might be issues over whether the trustees’ grant decision covers it.

If the project is still furthering the same aims and achieving the same outcomes for the same target group, my experience has been that trusts have been okay. However, you could do all of those things and still be making a major change which might make the trust wonder about whether they need to go back to the trustees.

As project management guru Ricardo Vargas highlights, there’s a case to be somewhat resistant to change, to stop the project unravelling. However, it’s usually plenty enough if you highlight that the proposal was an agreement between Fundraising and Services; and that changes potentially need agreement with the trust (who’ll have limits). Services are used to delivering to service specifications, especially if they handle tenders.

Clearly, though, you don’t want to block improvements, changes that definitely need to be made, changes of detail that the trust will be fine with or things that could be argued as within the original specification.

My starting point is always: how will it affect the impacts, as this is the key issue.

A good way to unpack a change is to use the 7 R’s framework from change management theory:

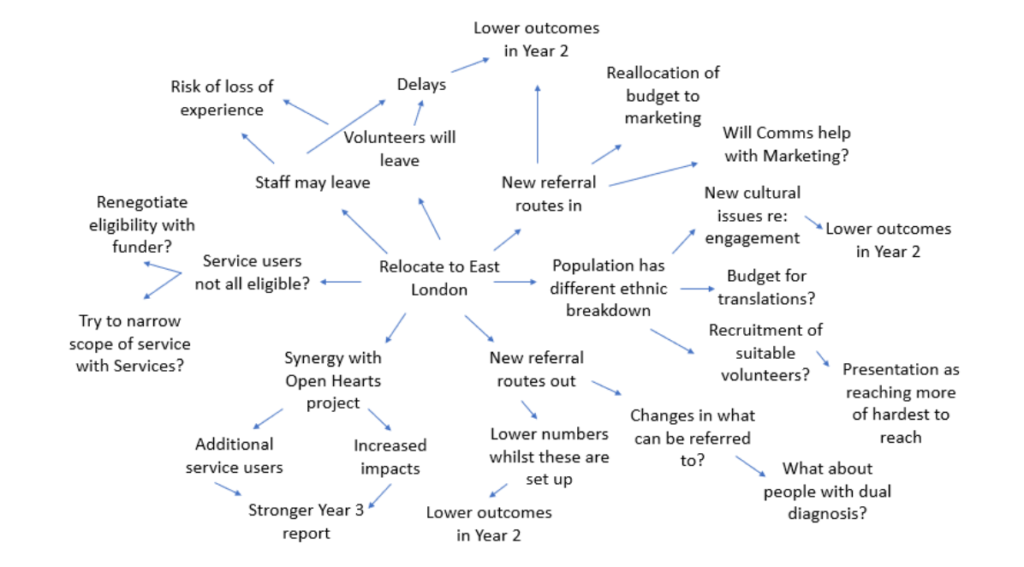

If it’s complicated to think through, a nice tool to help you is the “futures wheel”. (It’s referred to as a wheel, because it the future consequences that you’ll plot out will spread out in a circle, from a hub which is the proposed change that’s under consideration.) You can do a futures wheel with the Services manager or on your own to see what this means. The consequences of each change are spelled out, building a bit of a web of issues to look at:

Garfield Weston Foundation is one trust which cares more about project changes, but in the words of Director Philippa Charles: [what turns them off is] ‘Not doing what you said you’d do. Keep us in touch with what’s happening… Report on time when we asked you. Tell us if something has changed. Share with us your learning… Not everything goes to plan, we understand that. What is a bit of a killer is when there is complete silence and we find out things after the fact. Those are the obvious things that would cause us to pause for thought in terms of any future application. [Change] is not uncommon… If something changes we would want to know about it.’

This is another term coined (I think) by Josh Kaufman for The Personal MBA. The idea is that we’re biased in favour of intervening when things go wrong. In law, this might be how we’ve gone from someone successfully suing McDonalds when they burnt their lip on a cup of coffee to, now, any drink you buy saying on it “Caution: may be hot”. Sometimes it’s actually better not to intervene.

That’s not always a great message for a trust fundraiser. If things go wrong on the project, if you’re like me then you’re emotionally tempted to go back to the funder and say: “This thing happened, so we instigated a full investigation and introduced the following changes at the following different levels…” It makes it sound like you’re a responsive, learning organisation and you probably taken seriously the need to deliver what you said to the funder you’d deliver. However, in the bigger picture, sometimes it’s better not to change things, or not to change too much. So in the real world, there’s a balance to be struck.

One thing that might look like is: when things go wrong, still having a discussion with Services about making changes so there’s something positive to say to the funder, but actively “reality checking” with them that the proposed ideas you come up with together aren’t onerous and making things worse.

Changes which are outside the aims of the project will be a lot harder to agree with the funder than changes that further the existing aims of the work.

If the change is major, it’s tempting to try and get the team to deliver a huge amount of the new work so that it impresses the funder more. However, you’re effectively going back to the initial, slow period of the project, where people usually start small and get things right. So, if you promise less to Services, you’re likely to put the service back on a secure footing again.