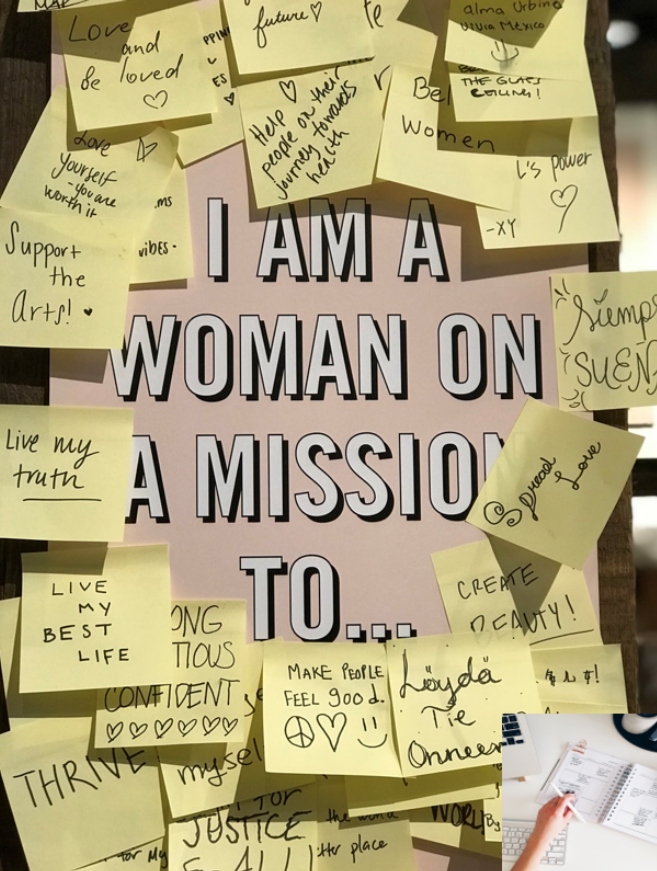

Photos: Valentina Conde and (insert) Scott graham on Unsplash

This webpage is for trust fundraisers with three or more years’ experience. Beginners should use this page instead.

Photos: Valentina Conde and (insert) Scott graham on Unsplash

This webpage is for trust fundraisers with three or more years’ experience. Beginners should use this page instead.

‘Grantmakers reported that they have particular trouble interpreting the budgets that they receive from nonprofits and often create strict budget formats and templates to get comparable and interpretable financial information. As one survey respondent commented, “We used to allow agencies to submit the budget in their own format, but it has been so challenging to figure out how some things were calculated, and [we spent so much time] reconfiguring the budget for presentation to our board, that we now require agencies to use our format.”’ Drowning in Paperwork, American report, 2008

There’s a separate page about constructing a budget. This section is about how to present a budget to the funder.

If the funder will part fund the work, understand what stage the funder comes into the project

Some funders are happy to come in early, some towards the end. That’s a question for your phone research, normally. It affects what you’re applying for. For example, a funder that wants to come in at the start could be presented with a new Information Officer that you’ve just started fundraising for. However, a funder coming in only when ¾ of the money is in would never fund that post standing on its own, but they might contribute to the full Information Team of four, including one new one.

Ha ha ha – okay, basic point, which isn’t the aim of this site. However, there are slightly less basic consequences:

The number of times I’ve taken over someone else’s budget and been unable to update it at Stage 2 of the application, or report against the costs. You know how to communicate clearly to others. It’s perhaps your single most basic skill. Good notes might also help with internal approvals.

It’s doubly important that you do this for a new project that you helped write. The Services team will be using the budget for expenditure purposes and if they don’t understand bits of it, they’ll be at sea about what the assumptions about expenditure were – even if you talked it through with them back when the budget was written.

There are two sides to this:

A couple of points people ask about:

There is no one “right way” to do this with funders. As long as what you’ve done looks like common sense to a funder, you should be fine. If in doubt, you can ask the funder. (Just be prepared for sometimes slightly waffly answers.)

I work at a charity with slightly higher overheads (including support/central admin staff and apportionment of office costs, they’re equivalent to 34% of the Services team salaries in a budget). My colleagues/predecessors have just put these in the budgets in full. I’m not aware of us ever being turned down on this ground. (Which isn’t the same as saying we haven’t, of course…) You could ask your funder – but if you really want to know a level, “What level so overheads have applicants typically come with that you’ve funded?” might give you a figure, whereas “What would you fund?” is more likely to give you some general principles.

As a grants assessor, after a while you have a vague idea how much things might cost. For example: I once got turned down for a mentoring project because “it was expensive for a volunteer-led project and a mentoring project”. (You could argue that’s a reason to sometimes have a lower level of organisational cost recovery?) On the other hand, there are plenty of examples of trusts saying they don’t want to fund things to fail because the budget was too low.

How to address the issue of what’s “just the right size of budget”?

Occasionally, budgets use language that only appears once or twice in the application. Given that the assessor won’t be remembering all the fine detail of what you said, this makes it confusing.

As an assessor, when I don’t understand a proposal, I’ve usually gone straight to the budget – because then I can see what the actual elements of the work are. Also, budgets are more likely to get queried in the grants meeting (when, most likely, no one can remember the detail of the project). For both reasons, I’d recommend you especially write the budget in a clear way, that’s easy to follow without appreciating the intricacies of the project.

“It’s not all about the writing: budgeting”

Amada Day and Kimberly Hays De Muga do Fundraising Hayday podcasts for an American audience that are funny and sometimes have a bit of more advanced material. Four of the headings in this web page were prompted by the above podcast. They also do good coverage of the basics. Be aware: this is an American podcast and some of the rules and practices with big funders are different from the UK.