Photos: Katt Yukawa, Carl Heyerdahl and Ryan Franco on Unsplash

This webpage is for trust fundraisers with three or more years’ experience. Beginners should use this page instead.

Diane Leat’s classification

In the early 1990s, Diane Leat proposed three categories of trusts, which are arguably a little basic for inclusion in this site, but I think would still add a little clarity to the thinking of some experienced trust fundraisers. Her argument wasn’t exactly that this was how you could divide trusts, it was more that it was effectively how trust basically behaved – in three ways – but that they didn’t realise this reality and got confused in places. All the same, I do think it’s a good “rough and ready” division:

Gift givers make many grants and do not think deeply about individual grants. When you personally approach someone with a collecting tin, you probably aren’t going to grill them about project management issues at the charity they represent. It’s more a quick and gut-level process. You can recognise a gift-giver when you open their grants list and the income is distributed in relatively large numbers of relatively small, similarly-sized gifts. Her criticism of trusts in this group was that they sometimes tried to ask too many questions – but there’s a clear separation from the following group…

How do you think you could make a quick impression of the right kind with your proposal for this group?

“Grant makers” are thinking of the most effective way to make a difference against their objectives (e.g., ‘to help make the arts more accessible by developing new audiences’). Most likely, they will make different size grants according to the circumstances and ask more questions to help them take those decisions. (Please note that Unwin was using “grant maker” in a very specific sense, that is different from how trust fundraisers normally use it.)

They have more interest in communicating well with you, as it means they will get presented the right funding opportunities to make the biggest difference. However, something that is implicit with all trusts is doubly the case, here: they aren’t that interested in you as a charity, only in what difference they can achieve through you.

Investors in organisations. These are more focused on the organisation as the best judge of how to make a difference. Where “grant makers” wade in and say “this intervention makes the most difference”, investors are delegating that to the people they fund. They might (or might not) back the charity they fund for an extended period and then withdraw.

I’d want to divide this “investors” group in two.

- The first is trusts that are actively, strategically doing this – quite a small number, who need careful examination because they don’t behave the way a trust fundraiser might normally be expecting. They’ve been amongst the trusts most open to meetings and extended discussions. Think of the Pears Foundation, for example.

- The second group is Bill Bruty’s “zombie trusts”: trusts who write the same cheques every year and who are hard to “get into”. The main thing when you’re on the inside is probably not prompting them into actual action (i.e., looking elsewhere).

A couple of qualifications to the above narrative. Firstly, Unwin was proposing this split as a way trusts should think, rather than saying it was exactly what she saw. (When people are doing things in isolation as a hobby, you wouldn’t always expect clarity from them.)

Secondly, she recognised that the behaviour of trusts can blur between categories. So for example, a trust may fund a wide range of organisations and projects, but to an extent, if you look at their giving over the years you can still spot “clients”. They might like to support those charities every so often, whilst retaining more freedom in who they support.

The way you approach and report to the different categories of trust, their needs and the depth of relationship you can have with them differ by nature.

An interesting example of gift givers and grant makers in the real word… I helped two different charities in the same Borough, based a mile from each other, that described their service users in very similar ways and that had similar aims and not unrelated services to achieve them. However, one wrote proposals that would appeal strongly to grant-makers (good detail on services, lots of SMART, good value outcomes). The other wrote proposals that fitted the gift giver approach (short but more superficial and actually more vague, with good stories and a clear immediate impression). Both had many dozens of trust funders each year (the gift giver-style charity had more cash, but I think because of some lucky advantages – the grant maker-style charity would have “won” otherwise) but actually only 10-20% of the names were the same. Both actually had grants of all sizes.

Bull and Steinberg’s classification

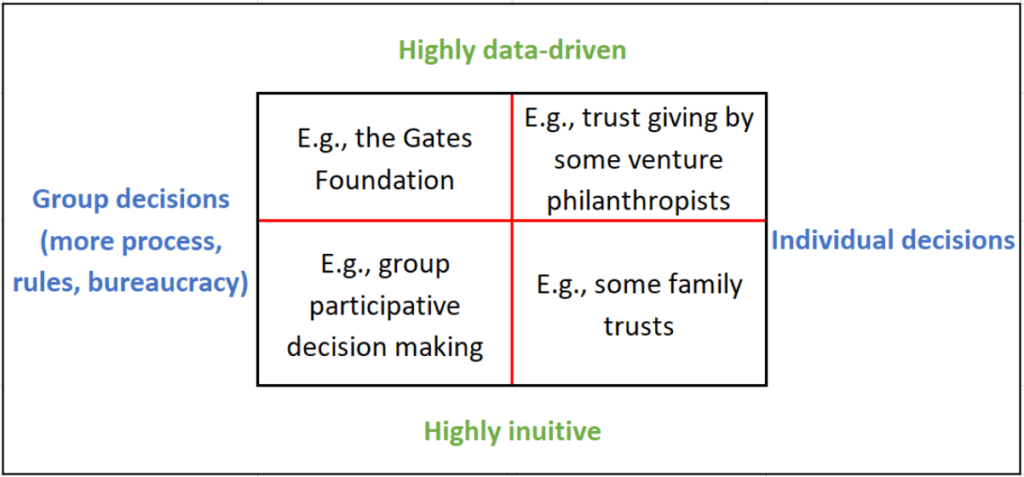

These grants officers came up with another, related, classification for their 2021 book on modern grantmaking practice:

This seems a useful model when thinking about both researching and trying to influence the trust.

Going back to my two charities in the same Borough, you could have characterised one as appealing to data-driven fenders and the other to highly intuitive ones. However, some of those intuitive ones would be seen as very “old school” – so, don’t confuse “intuitive” with “new age”.

Different distances from the cause

I was in an assessment meeting today where, unusually, there were a few Community Foundations. It was a reminder to me that there are trusts around who are much, much closer to the realities of the situation than others. They were able to discuss the organisations in ways that you’d never hear even from people who’ve funded the same group a number of times:

‘She’s hard working but just needs that bit of encouragement to take them on from where they are.’

‘They’re working hard under very difficult circumstances.’

‘The Coordinator is technically really competent and very determined. If you give her the money, she’ll deliver and make good use of the funds.’

‘I’ve visited the project and the area is incredibly deprived, but set right next to very wealthy areas. So, they’ve got that to contend with, too.’

It was like that at Age Concern: the Field Officers knew the groups pretty well. Ditto at Help the Aged, we had one or two staff who’d met the key staff with a lot of funded groups, as well as knowing the work and the paperwork well.

I’ve occasionally had this with trusts – or example, I was once assessed for a homelessness project by someone whose “day job” was as CEO of the London Homelessness network. On another occasion, it was by an academic in the field of work we were applying for (addiction).

I don’t think that means, though, that as an outsider, you always stand no chance. Many grants officers have concerns for fairness and do like to give to new groups.