Photo: Marcus Aurelius

This webpage is for trust fundraisers with three or more years’ experience. Beginners should use this page instead.

Photo: Marcus Aurelius

This webpage is for trust fundraisers with three or more years’ experience. Beginners should use this page instead.

As trust fundraisers, we’re paid to be a translators. If you “go native” at the charity you work for and start using the same jargon and assumptions about what’s important as your Services colleagues, it will lose your charity money.

One of marketing guru Seth Godin’s big points is that people will only be interested in you if you are set up to serve them. If you purely seem to be flogging something for your own purposes, there’s less appeal to the trust. How far can you make it clearly about them, about who they are?

Advertiser Mchael Masterson suggests people consider the BDF formula as a way of really taregtign them well:

Beliefs

How do they perceive themselves? What do they think others think about them? Where do they position themselves?

Desires

What do they want to become? Where do they want to get? What is their ultimate goal?

Feelings

What are their emotions in regards to their business? What are they proud of? What are they scared of? What part of their business worries them?

As advertising copywriting guru Robert Bly says, you don’t need to do expensive market research at this stage, because you probably know a lot of it. However, the following summary of relevant research should give you a better overview, again.

There’s a case for trying to develop a sense of a number of stereotypical characters that you’re addressing, what in other fundraising contexts are called “personas”. Personas are individuals with a particular issue that’s relevant to you. Reiss (2018) would argue that it’s by seeing the differences from those stereotypical characters for each individual that you establish real, accurate, empathy. So, that’s the ideal when we can manage it. However, we often can’t do that – and I think it’s useful to have a “persona” that the actual trustees can differ from, as a point of reference.

The people we’re focused on are fairly anonymous and uncommunicative, though. How on earth can you convey proposals in terms of their worldview, fitting their attitudes and proclivities, when we don’t know who they are?

There are some great clues. An Association of Charitable Foundations analysis of Charity Commission data about Trustees is well worth reading (Lee et al, 2018). A very valuable aspect of this survey is that 70% of respondents were from trusts giving under £100k a year. Much that you hear from trusts is dominated by the big, professional grant-makers, whereas this survey seems closer to the majority of trusts.

Some of the most significant points are the following:

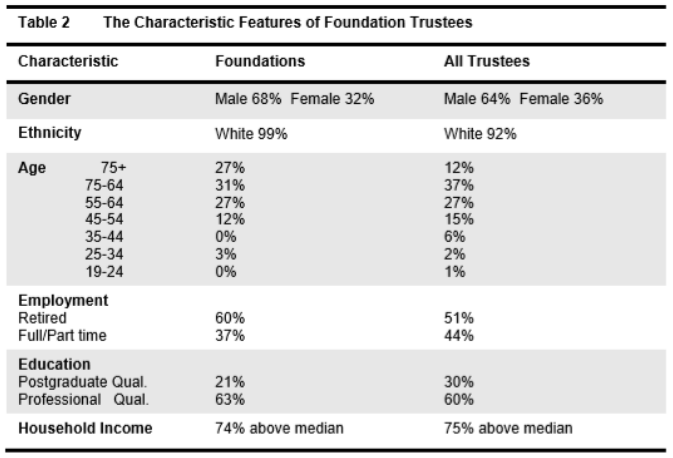

Lee et al, 2018, p.4, Table 2

63% of trustees say they are educated with “professional qualifications”. Googling the names of trustees throws up a lot more lawyers, financiers, company directors and accountants than it does social workers, nurses or museum curators – except in some institutional funders, where names of experts such as charity CEOs and academics can occur. In the States [where the sector is admittedly culturally different to the UK] Edgar Villanueva describes the sector as ‘The whitest, most elite sector ever.’

A 2022 Foundation Practice survey found that, even amongst that segment of the trusts market who do self audits, trying to improve the diversity of trustees and staff was very low on their to do lists.

While the partners of entrepreneurs can be the chairs of new trusts from that background, David Callahan’s The Givers says that the values behind the foundation are nearly always jointly agreed by the pair.

When you are writing, are you imagining trustees – the likely decision-makers – as older, white, professional males? How do you imagine they would see your service users? Your charity? Your proposals? How would you know if you are probably right?

In the States, Inside Philanthropy looked for the 100 people with most power in the sector. Quite a lot were actually entrepreneurs, with the kinds of worldviews entrepreneurs have. I’m not sure that’s so true in the UK. Certainly, the people you see speaking at events and doing pieces in trusts’ professional press are the directors of foundations, often the big ones.

In his book, Decolonizing Wealth, longstanding foundations staffer at large foundations in the USA, reformer Edgar Villanueva says: ‘‘The field [of foundations] is adamant that it know best. It fails to get with the times, frustrating the younger folks. It does not care…. ‘Philanthropy [changes] at a glacial pace.’ In 2021, nfpSynergy interviewed leading staff from UK funders umbrella bodies and from the more radical/progressive UK trusts. Some interviewees ‘conceded that funders still operate under a 19th century philanthropic model that is becoming increasingly unfit to serve today’s changemakers.’ Bull and Steinberg (2021) in the UK rather pointedly refer to best practice as “modern”, as opposed to “traditional”, grant-making.

There certainly IS funding of modern approaches to service provision, such as the spate of initiatives to fund IT developments to services during the COVID pandemic. However, a number of trusts have remarked on the difficulties in assessing IT projects and it is unclear to me, certainly, whether these funders are still in the minority.

Many years ago, the Directory of Social Change produced a report on funding of BAME issues that was highly critical of the sector. highlighting what they then saw as a very low percentage of grants given to specifically BAME work. How far have things changed? I’ll take the UK and the USA separately, here.

In a survey of grant-makers by the UK-based Grant Givers Movement, over 40% of respondents had witnessed instances of prejudice or discrimination of some kind. I haven’t at all, personally, btw, though I’ve been more of a dilettante in the grant-making sector. 40% is a minority – though it’s worth bearing in mind that membership of professional bodies (e.g., the GGM) tends to come from the bigger and often more liberal trusts.

A 2022 report by UK organisation Centre Black, into the experiences of charities where most of the staff were black, found ‘Black-led impact organisations have largely negative experiences with funders. They believe the involvement process is mainly tokenistic with funders placing little value on lived experience.’ However, this comment was not directed at trusts specifically and suggests a wider issue of racism.

This all possibly fits with the attitude survey, below, that finds older men (i.e., our target market of trustees) are less likely to recognize that racial discrimination holds people from BAME groups back.

In his book, Edgar Villanueva thought that the discussion of “decolonizing wealth” hadn’t gotten anywhere near as far in the UK as in the USA – and he’s very critical of things in the USA.

My actual experience in the UK is a bit different:. Fundraising for a youth charity for Somali girls was that it was as easy, if not easier, to fundraise from the more “right on” organisations – the easy end of the market – if you can talk the talk and present projects strongly. This squares with numerous minutes of the Big Lottery Fund’s grants committees that they struggle to find enough BAME applications of good enough quality. I haven’t had a lot of opportunity beyond that.

I do also have a bit of relevant experience with philanthropists, which shows them in a positive light. In the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter protests, a giving circle I was sitting on had three projects presented to it and one was a BAME youth group. The woman who ran the organisation cam on and basically gave us an angry political diatribe, hectoring the audience about white racism in a way that reflected on us. I remember worrying for her – I thought she’d completely blown her chance of getting the money. Actually, her group raised more than the other two projects! Is that about my giving circle, that moment in history (trusts do respond to big things in the news) or what?

Looking to the USA (and he thinks we’re worse:) Villanueva says that there are more reports on issues like funding of BAME groups than actual change. He says in an interview in Inside Philanthropy, with regard to changing cultures within foundations on BAME issues, ‘Tradition and the status quo are worshipped, resulting in conformity, formality, and arrogance in many organisations. Anyone who pushes against that culture immediately becomes a target.’

Villanueva argues that the lack of diversity in foundation hiring, and lack of social ties to non-white communities, has led the philanthropic sector to reinforce racial inequalities as much or more than it remedies them.

Villanuaeva says, ‘I was in one particular meeting with about 30 folks who work in philanthropy. And it was a very painful conversation. People were literally in tears — especially people of color working in these institutions — because of the lack of being able to have a transparent conversation.’

He cites a colleague saying: ‘I’m always trying to play that game of chess, as an Asian American woman, as someone who’s a mid level professional, and where do I push some of the assumptions, versus where do I not rock the boat because I just make things harder for myself.’

A US survey of grants officers found that the Black Lives Matter protests had heightened the urgency of addressing BAME issues (and Villanueva said in a recent interview that discussions about what to do were very much alive in a lot of foundations). Gemma Bull also talks about leaders pushing back against discrimination and there is some of that in Trust and Foundation News and ACF conference talks.

Other parts of Fundraising

Different causes have different attractions and you can pick some of that up from other teams who have more contact with their donors. For example, people funding the arts are more likely to be looking for fun and exciting experience, whereas if the funder is closely focused on medical research in a field, or on addiction, the chances are the founder (if they’re still around) had a close experience with it. Most trusts fund a wide range of causes and some of their priorities they’ve simply inherited and they may have become more educated in the issues. So, the attitude of trustees can diverge from those of active individual donors. However, other parts of fundraising can at least provide interesting pointers or things to consider.

Age-related points

An article in the The Journal of Experimental Social Psychology explained that young people often have difficulty judging the emotional states of older people. If you’re a trust fundraiser in your 20s or 30s, you may want to spend more time with your parents and grandparents and to discuss their attitudes towards charity and your cause.

However, there may be some useful clues about the attitudes of older white men in online research. For example:

There’s also a literature on marketing to baby boomers. For example: older people grew up in more of a culture of self-reliance and can see later generations as having more of a sense of entitlement. While they have lived through change and believe it’s important, they can be sceptical of fads and expect proof. (Kennedy & Kessler, 2013).

Marketeers writing about older people highlight that, with diminishing eyesight, they may not have such a good shopping/user experience. As I’ve entered my 50s and needed glasses, so it irritates me more when people use small fonts, or colours with lower contrast. My prescription isn’t always quite right for my eyes. (I can work round it by blowing up the page, though not if it’s a printed copy.) Daniel Kahneman highlights that the best way to increase your success is to make things less difficult for people.

With age, short term memory deteriorates and recall takes longer. A lot of the trustees we’re approaching are professionals and a lot of professionals are very smart guys. However, I wouldn’t be surprised if fundraisers overestimate the amount of a proposal that people are going to remember when they are in the awards meeting. This might be even more true if you’re a trust fundraiser in your 20s or 30s.

I’ve made various points about specific attitudes amongst over-50s. However, in his book discussing how to market to the over-50s, marketeer Dick Stroud, says the problem is generally not so much one of needing to market specifically to that age group as it is one of not noticing one’s own pro-young people biases and the adoption of distinctively young attitudes. If your idea feels quite trendy, for example, you might want to question if it will be shared by your readership.

In this vein: when I talk about appealing to values as a way of moving people on other pages, I’ll be starting with values that we ALL share.

Class-related issues

Also of interest is literature on marketing to people in the AB socioeconomic group. For example: wealthy donors have particularly high expectations of charities when determining which to support. For instance, a US survey from 2010 found the following factors were ranked among those most important by high value donors when determining which to support: Sound business and operational practices (87%); Acknowledgement of contributions, including receipts (85%); Spending an appropriate amount on overheads (80%); Protection of personal information (80%).

A 2017 paper, Both selfishness and selflessness start with the self, Whillans et al. found that wealthier individuals are more likely to give money when presented with a request that appeals to their sense of independence and self-reliance.

Anand Giridharadas, a left wing journalist who studied modern foundations in the States, highlights that the “thought leaders” amongst the “givers” are people whom he refers to as the “takers” (entrepreneurs people who’ve made a lot of money, benefiting from the work of others to do so but paid a minimum of taxes). That means that certain interventions aren’t likely to get funded, because those people aren’t likely to believe in them.

A test of that might be: do they fund welfare benefits take-up projects? I’ve not had trouble funding advice projects for older people (where benefits advice is a big component) in the UK. At the same time, it’s interesting that out-and-out poverty relief advice, such as CAB advice services, aren’t that widely funded by trusts.

Also, to cite a Barclays study into High Net Worth Individuals (HNWIs) and charity: ‘some wealthy individuals expect charities to conform to especially high standards. For one thing, their status as charities carries unrealistic expectations of the organisations’ moral integrity, while at the same time demanding them to be run with high levels of business-like efficiency and a sense of financial prudence that would be rare even in the commercial sector.’ It would be interesting to know how far the trusts who look for low overheads are those dominated by wealthy individuals. Having just come from a charity with high success rates despite having about 20% in its overheads requests to small trusts, I wonder, however, how widespread this attitude really is in our trusts. (We had great targeting and a great ask, though and you could argue that maybe we’d have done better again with lower overheads…)

In the What Donors Want podcast, Emma Turner, adviser to HNW philanthropists, says ‘Wealthy people expect certain levels of service… no one is asking charities to over-serve, but serve. Do your bit and nothing should ever go wrong.’ She said that would include things like a timely report.

On top of this, there is also a degree to which wealthy individuals expect the highly skilled professionals who run these organisations to accept a ‘moral salary’ in lieu of market pay.

Again, the Barclays report hints, HNWIs, like some trusts (from their comments in Trust and Foundation News) are perhaps overly focused on the leadership of a charity, whatever the way the charity actually runs or what the donation is actually going towards.In the States, Edgar Villanueva says some grants staff are overly focused on “rock star leaders,” who aren’t necessarily the people creating change. I’ve seen a mixture of body language when introducing my CEO to grants staff, from “Oh, good” to “Nice to meet you – now, let’s go meet the people who’ll enable me to do my assessment.”

In the States, Prof Paul Schervish has studied major donors and believes that today’s entrepreneurs (significant numbers of whom are either setting up new foundations or have effectively pledged to do so) have great self confidence, have a sense not just of agency but of hyperagency. Quite a few, for example amongst those from the tech industry, have upended their industries. Coming with that sense of hyperagency, they are far more likely than the rest of the population to believe they can have a significant impact on a social problem through philanthropy. Analysing how they speak about their philanthropy, he thinks that for them, becoming a philanthropist can be part of a moral or spiritual journey (rather than being predominantly about, say, tax).

It would be easy to speculate that maybe trustees are self-selecting as the socially concerned and therefore more left/liberal-leaning older people. I sat in a meeting of a high net worth giving circle, including a number of small trusts, in the aftermath of Black Lives Matter and they’d brought in a BAME youth group. The coordinator absolutely hectored the audience from a standpoint of discrimination and power relations and my instinct was “Oh no, she’s blown it with the audience.” She actually raised more money than the other two groups pitching that evening.

However, when you look how little money normally goes to BAME causes, or how the money going to Oxbridge dwarfs that to literacy causes, or the grants to charities like the Tate dwarfs grants to community arts, I’m sceptical that trustees are “right on”. I think it’s actually a liberal prejudice that the only people who care about social issues are on the Left. It’s something that 10 minutes in a meeting of a Tory-run council or a Residents Association in a rural area should disabuse you of.

When looking at the chances of getting a grant, it’s at least important to take out as a factor all the donations that are associated with the trustees’ affiliations, rather than their other motivations for doing good. So as an arts fundraiser I’d ignore grants to the Tate or the Royal Opera House when setting my targets, a schools fundraiser I’d ignore grants to Eton in the same way, a universities fundraiser grants to Oxford, a museums fundraiser grants to the founder’s local museum, and so on.

Dowie (2001) suggests that large US foundations actually go through four stages:

I’ve seen a bit of that over the years in the UK. If you were to compare photos of trustees of a small trust with those of a grant-maker like the Tudor Trust, there’s an obvious difference with Tudor from your typical pictures of mainly older white men. (Of course, as we have more time and information to investigate big trusts, we don’t actually need as many orientating generalisations.)

In his book The Givers about major US philanthropists, David Callahan (editor of Philanthropy magazine) notes a change when the person setting up the foundation dies and their children take over:

I’ve come across occasional trustees who are entrepreneurs or the children of entrepreneurs whose giving is affected by entrepreneurialism: they like an entrepreneurial spirit, and/or the approach of deeply understanding “the market” (in this case, service users) and having shaped the work closely around meeting their needs. (At a guess, maybe ¼ of trusts are actively influenced by an entrepreneur, though not necessarily to be “entrepreneurial” in the above sense.)

Perhaps more importantly for us, I think, than the venture philanthropists in David Callahan’s book is another group of founders of trusts. Regarding these, the market research into attitudes of people who create substantial wealth seems relevant. Quite a few of the interviews I’ve read about founders have concerned first generation wealthy individuals and (if American research, gathered together in Stanley and Danko’s The Millionnaire Next Door is reflected in UK founders) the large majority of dollar Millionnaires (in terms of accumulation of wealth, with which you could found a trust, rather than affluence) come from at least somewhat more modest backgrounds than you’d expect and their values very different from the way they are presented in the media, in ways that potentially impact on our work:

I’d never try and over-sell the value of the above advice to us. The great majority in the sample in the research believe that charity begins at home”. However, it’s interesting, nonetheless.

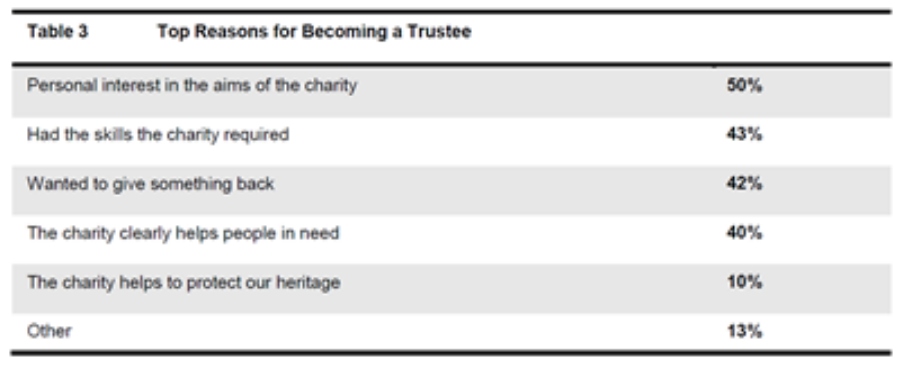

Lee et al, 2018, p.4, Table 3

There is a lot of evidence that generosity makes people both happier and healthier (e.g., Sargeant and Sheng, 2017 p.112). Trust fundraisers can be cowed when considering talking to trusts – but actually, we’re doing them a favour by helping them be their best selves! As my editor, Robyn McAllister points out to me, as fundraisers, we’re ultimately giving donors the opportunity to be part of the solution to problems they care about – which is a pretty powerful proposition. Major donors guru Rob Woods tells stories of major donors who said they’d had the greatest experiences of their lives in giving.

Bill Bruty highlights in his course on accounts that if you put 20% of the shares of a UK company into a trust, it provides some protection for the company from being sold off. That means you could potentially have trustees involved who aren’t that interested in the hard work of giving.

The obvious answer is: it’s their job as members of a grants committee. In that sense, your application is saying: “Giving to us is the way to do your job well.” This is a pretty rationalistic approach.

However, trusts (admittedly, normally the staff) are often quoted as saying they want to be moved, as well. I’ll spend some time discussing this more subtle motivation. Watch Fundraising Everywhere’s videos of people giving grants. They are clearly being somewhat moved, despite the slightly drier nature of the field of giving, as well as applying principles. I expect they are mostly being moved by the same emotional processes, because they are trying to change lives just as any individual donor is.

A challenge is that trustees aren’t necessarily giving to things they would fund, personally. Sitting on grants panels, I’ve (happily) made grants to things I wouldn’t donate to myself and given the range of interests of many trusts, that’s probably true for most trustees. So, how relevant is the (huge) literature on motivations behind individual giving? People on grants committees still clearly have a feeling for the work they’re choosing. I’d suggest the feeling of choosing to support isn’t so far from the feeling of choosing to donate, though there are other elements, such as a sense of obligation to your role.

If we do accept, though, that motives for individual giving are worth bearing in mind, the best discussions of this I’ve seen are by Jen Shang, formerly Professor of Philanthropic Psychology at Plymouth University. There are a few nice videos online, from her and her collaborator, Adrian Sargeant.

I’m just off to an assessment meeting on the day of writing this. The projects I’m most interested in I do feel more emotions about – and that’s my immediate memory of them (though I’ll remember a lot more in the meeting, as we have longer discussions than many funders). My emotions are quite different for the projects:

Sheng and Sargeant say that when a donor is very involved in the decision, both their cognition and their emotions influence the decision. Isn’t that the world in which we’re, also, working?

The discussion on other web pages of behavioural economics and of rhetoric highlight compassion as the obvious emotion. However, in Fundraising Principles and Practice, Shang and Sargeant highlight the role of place of joy – the more joy in knowing the difference they are able to make, the more likely they are to give (p. 98). They highlight that it is the certainty of making that difference that elicits joy. This seems particularly significant when you consider reapproaching a funder for the same project – how the report and fresh proposal complement each other.

They also mention hope, which in behavioural economics discussions is treated notably as less motivating than joy: the difference is that when the outcome is uncertain there is hope, when it is certain there is joy.

They also highlight that people give out of anger at certain situations (their example is Mothers Against Drunk Driving, MADD, a US pressure group). Other motives they mention are: self-esteem/self-interest; altruism; guilt; pity; social/distributive justice; empathy/sympathy; fear; prestige; and making a difference.

There are different ways you can look at how people form their attitude towards giving to you:

Interestingly, Sheng notes research has found that attractive people are perceived as more worthy of support and that female subjects are deemed more worthy than males and that individuals who could not be blamed for their condition garner more donations than people who are (Sargeant & Sheng, 2016 – the actual research dates from the 1970s and 80s, but perhaps we can see a bit of the same attitudes in society today).

For some causes especially, it may also be worth considering the benefit the donor gets from the gift. This is a lot clearer for a major donor-led trust giving to an arts organisation that his wife chairs, say, but the “warm glow” of having made the gift is much more general. You might want to consider five possible categories of benefit your trust personal might get:

Adrian Sargeant also uses self-enhancement theory when discussing people’s giving. He says that Katz and Beach (2000) tell us that people are most likely to seek partners who give them both verification and enhancement, and that in the absence of the latter, they seek the former. He then asks: ‘How can fundraisers can stretch their donors’ imagination about just how good a human being they can be?

I’ve both read and heard trusts talking about getting bored seeing the same old work every year. I’ve increased the giving from trusts with potential to give more by changing the project from one they’d been funding and I’ve seen other trust fundraisers do the same. The clear risk for us, though, is that we do not understand the trust well enough to make the change. Sargeant and Sheng also highlight another risk from individual giving: donors get into habits and when you make changes they can re-evaluate their relationship with the organisation.

Adrian Sargeant gave a recent presentation where he highlighted that the emotions of donors and other their reasons for giving actually differ from charity to charity. I’d think it’s worth speaking to your colleagues in Individual Giving, if you have such a post/team, to see what they know about perceptions of your cause.

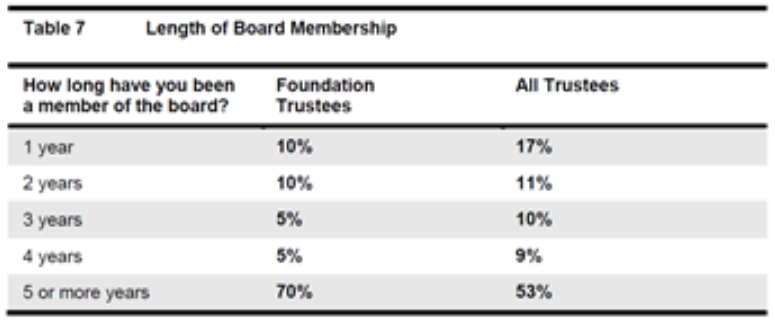

Lee et al, 2018, Table 7

A couple of points about the extended tenures of many trustees:

Vanessa Kirsch, founder of “venture philanthropist” organisation New Profit Inc in the States, observes that, from their conversations, major donors are often disappointed by the degree of impact that their philanthropy has had.

That’s an interesting comparison with Rob Woods’ claim to have found that, stewarded skillfully, involvement in philanthropy is capable of giving donors the most amazing and fulfilling experiences of their entire lives.

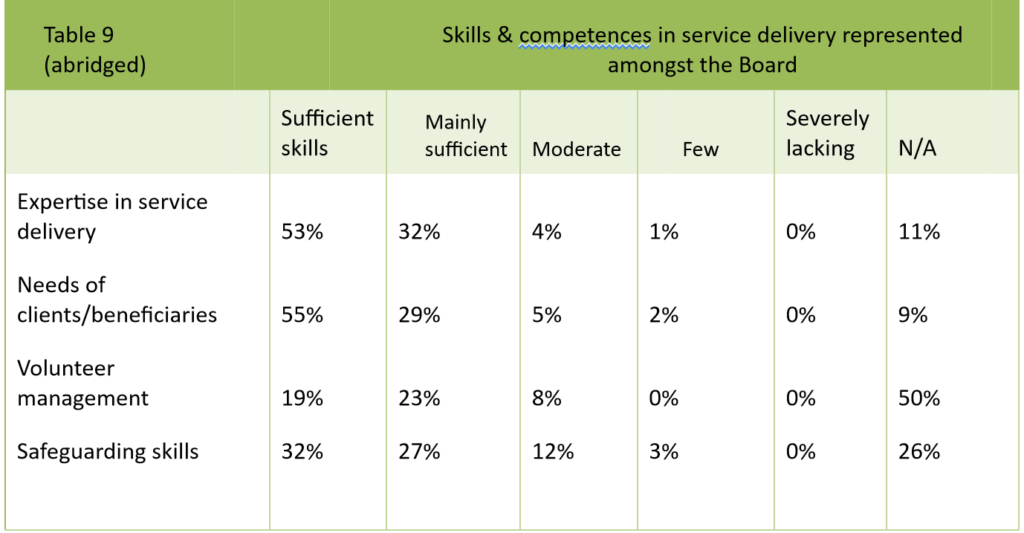

The table below describes how trustees saw their skills in service delivery and the needs of beneficiaries – i.e., the issues your proposals are about.

Only just over half think they have the necessary skills and the figures drop off even more when it comes to specifics like safeguarding and volunteer management.

We have seen that, very likely, a lot more Trustees are accountants, or lawyers than social workers, curators, medical researchers or low-income service users (i.e., close to the cause) as the ACF report says ‘[T]he vast majority of the sources of recruitment for new recruits to the board appear to be highly informal’. That said, there is more breadth of expertise in the big, institutional trusts.

However, the issues around expertise are more complex, again. As Pharoah et al highlighted, an individual trust often addresses ‘the needs of a very wide range of communities, groups and individuals, responding to highly specialised and difficult issues, as well as more general problems’ One trust can straddle many different fields of giving, from the arts to religion to health to social welfare to medical research. That is a lot of expertise to cover within one small Trustee board!

As a result of all this, as Hammack and Anheimer say, trusts can be making decisions on ‘only a cursory understanding of the fields and issues they address’ (2013) As Thea Monk, Chair of the Greater Manchester Funders Forum said about her body, ‘“What do you know about X?” If members of the Forum pick up the phone and ask this kind of question to each other, it will be a real win for the Group.’ (Trust & Foundation News, May 2021).

In the States, Chris Cardona, Program Officer for the Ford Foundation, says there’s, ‘[A] lack of access to lived experiences, which leads to assumptions about what folks’ needs are, what benefits are best for them, that doesn’t take into account that voice for them directly.’ [A small number of trusts, such as Trust for London in the UK, are actively pushing back against that and there is a small “participatory grantmaking” movement.]

Similarly, looking at the heirs who are taking up responsibilities in a number of the biggest US foundations, David Callahan notes that heirs can have training and expertise, having prepared for these roles, as well as ‘obvious empathy’. He notes that they can’t really understand the beneficiaries of the funded charities, though, because their backgrounds are so different.

I’m not sure things have professionalised quite so far in the UK.

It is worth remembering, though, that the more money a trust typically gives, the more likely you are to occasionally encounter a genuine expert assessing you.

In the Fundraising Everywhere grants meetings (with trust fundraisers playing the trustees) one project out of ten was rejected by everyone because they simply didn’t understand it (whereas the person shortlisting, who had come from an arts background, had understood it). Given that the trustees in these exercises were a diverse group of fundraisers, who might have more relevant experience, perhaps family/private trusts, especially, are rejecting over 10% just because they couldn’t understand them.

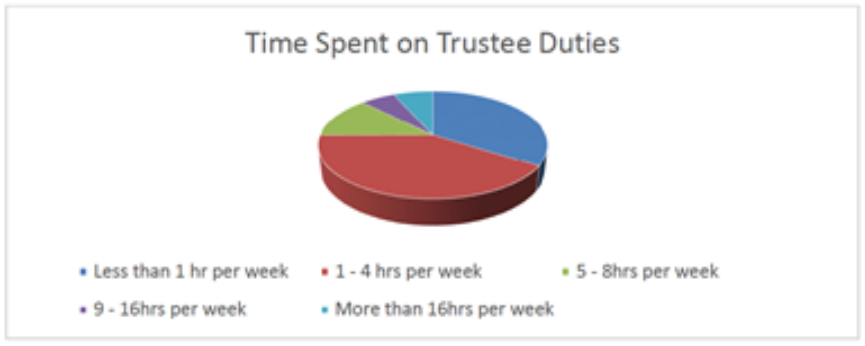

People are normally reviewing your application as a hobby. This is how much time the Trustees said they had to do all the work in the same trustees’ survey (quite a lot of the work is usually about applications):

Lee et al, ibid., 2018, p.8

How many applications do you have to look at? Doubtless that varies enormously. However, to give an example of the workload – I took 10 random (but not highly focused) Trusts giving £100k-150k. They would be trusts that would not normally employ staff. There is a great deal of uncertainty about success rates in the sector, but a success rate of 1 in 3 or 4 overall is often quoted. On the basis of 1 in 4, these hobbyists would be considering 36-464 (median 140) applications a year, in their spare time. As the applications can be sent out a week or a couple of weeks before the meeting, it’s a lot to get through.

As the Fundraising Everywhere panels found, the process at the grants meeting can also be very pressured. For example, the Peter Minet Charity’s board under its previous strategy considered 30 applications in 90 minutes.

I’ve just assessed eleven applications against five criteria (with a number of points to consider for each) in a day for a funder. you have to understand them, then you have to get to the bottom of whether you think they’re any good in the trust’s terms and then you have to compare them with each other – against all the criteria, in my case, because I was working hard at being fair. Even a little exercise like that was a lot of work, hard to get right and at the end I’m quite tired. You can see how people need things to jump out at them, how it’s a problem when things are convoluted and unclear, how assessors can lose interest when presented with high volumes of bids and how they can make mistakes. (I think it gets somewhat easier with practice – as you can do more of the work “without thinking”, but it still won’t be easy.)

A 1998 postal survey found that the chances of the trustees getting a summary of the work was significantly higher with big trusts. In other words:

In only a 27% of cases (with the same, largely small trusts sample) were the trustees told if they’d given to the cause before. Clearly, you should be reminding them, just in case.

As a trust fundraiser, the demands of your market can vary very sharply. I was very involved in one national charity that had a mid-six-figure trust fundraising income stream that it generated through what many would consider best practice in its proposals: clear and precise project descriptions, and precise enumeration of impact – numbers of service users, average change achieved across a range of measurements. Typical proposals for up to £10k could be a little longer: 3-4 pages in length, because they packed in a lot of (well written and clear) detail. Bigger proposals were longer again.

Later, I worked with a regional charity whose descriptions of its service users and the work were really quite similar, but that also had a mid-six-figure trust fundraising income stream that it generated through very different proposals: short (rarely more than three page) proposals with general descriptions of the service, including no figures (except maybe a figure for the number of users of the charity overall) and typically 2-3 short case studies as a way of describing the work, plus one full-page case study at the end. The second charity actually raised more (though I think because it had a stronger ability to arrange peer-to-peer asks – if you excluded those relationships, it would have done okay, but raised less. It was also bigger with more services.)

The most striking thing, though, was the different lists of names of funders. Despite targeting similar-sounding service users with related-sounding services addressing similar-ish issues (and being located about a miles from each other) only about 10-20% of the donors of one gave to the other and vice versa.

Just a few points that might be useful:

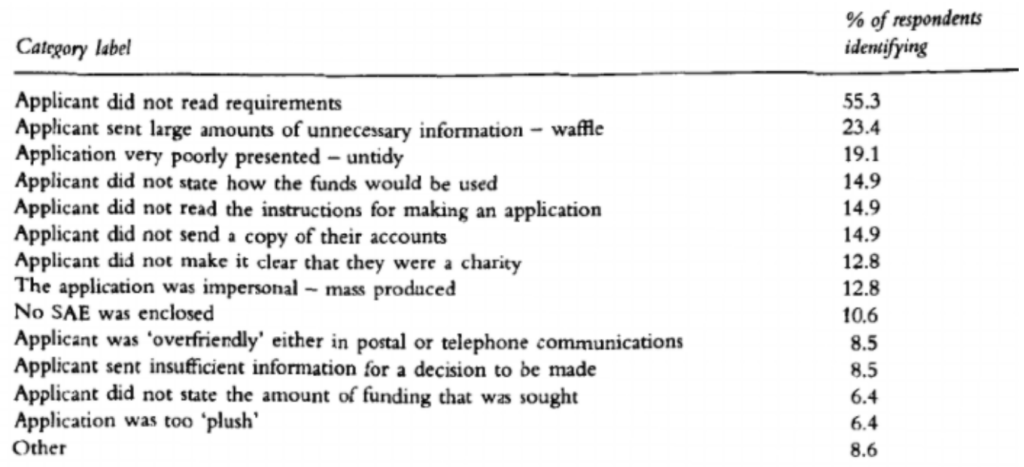

In the late 90s there were a number of attempts to survey trusts about this. The following was a good, representative sample of smaller trusts (just 4 out of 54 responses used gave more than £500k p.a.):

Apart from the reports mentioned above, there is a good set of podcasts on iTunes, called What Donors Want. Some of the interviews are with trustees, though normally of American foundations.

Edward Villanueva’s book Decolonizing Wealth is an excellent read as regards the experience of BAME staff working in American foundations and attitudes towards race. Not that much is of direct use for a fundraiser – it’s more just a slightly hair-turning book of general interest!

If you have significant opportunities with the foundations set up by hedge fund and/or tech billionaires, David Callahan’s book, The Givers is a fantastic read, extremely revealing if a bit journalistic, rather than careful, in its generalisations. Ditto (more UK-focused but less profound in its analysis) Paul Vallely’s Philanthropy: From Aristotle to Zuckerberg. I haven’t put this in the main text, because I think it’s still very fringe. However: in a nutshell, Callahan explores how these modern new philanthropists tend more to:

Tom Hall, Managing Director of Global Philanthropy Services at UBS bank, also said in an October 2021 Bright Spot talk that there’s a significant increase in philanthropy coming. He saw them as being from the kinds of people Callahan talks about. Tom Hall’s talks on Bright Spot are also excellent if you’re looking at that (currently, limited) target market, though he’s clearly quite focused in his thinking on overseas development. Hall particularly stresses the importance of metrics and ambition to sustainably solve problems.