Photo: Joe M Arthur and (inset) You X Ventures on Unsplash

This webpage is for trust fundraisers with three or more years’ experience. Beginners should use this page instead.

Photo: Joe M Arthur and (inset) You X Ventures on Unsplash

This webpage is for trust fundraisers with three or more years’ experience. Beginners should use this page instead.

The role of actual grants staff varies greatly, by size of the trust and the willingness of the trustees to devolve power:

‘If I wanted to say “No”, I could find a way. If I really wanted to fund you, I could often do the extra work [gathering extra evidence from the applicant] to get it to a “Yes”.’

Tim Cook, former Director of the trust that is now the Trust for London, once said that if he did not share the values of his Trustees, his job would be impossible. However, if you look the staff up on LinkedIn, they have very different backgrounds from their trustees. European research has noted the possibility of tensions between the trustees and their staff. In the States, an Inside Philanthropy 2020 survey of more than 200 program officers found that Foundation program officers feel largely aligned with their colleagues, but not with their boards.

The Directors tend to be from senior backgrounds, often CEOs of organisations in the relevant sector.

Grants staff below them are from more junior roles – former trust fundraisers, grants staff from other grants roles, occasional policy people, sometimes individuals from front line service work. At one time you’d have heard a lot of posh accents, but there are a lot more middle class graduates. There aren’t yet many strong regional accents, but there’s definitely social progress.

In the UK, Bull and Steinberg see ‘large numbers of talented, hard-working and highly motivated people.’ However, ‘Few jobs require such a wide mix of skills and knowledge.’

When looking at trustees, we saw the possibility in the UK that their class/professional and age backgrounds might give them different, maybe more conservative, attitudes (though there is perhaps a tendency towards assimilation more into the charity sector, with its more liberal attitudes, over the decades in the bigger foundations). These are the people who see the written presentations, especially summaries. However, their staff might, at times, be closer to mainstream charity attitudes. It’s interesting that the four recent books by staffers have been manifestos for reform.

Villanueva reported interviewing people (of colour) who refused to tow the party line and who had been forced out as a result. Bull and Steinberg in the UK also mention people suffering the consequences of speaking out.

One of the big insights of rhetoric is that if you want to deeply move people towards action, appeal to their core values. I speculate how far a good question would be: “What does your trust value most in an application?” However, the difference in background and views highlights a challenge when thinking about values. A trust is a community of individuals who do not necessary share (or need to share) values, just a mission and functions.

A lot of staff have been in the grants sector for many years – which either makes their experience rarified, or very experienced in both typical work and what can go especially well or wrong, as you prefer to see it.

In the States, ¾ of grants staff are women and ⅔ are white. In the UK, I suspect there are fewer BAME staff. In Decolonizing Wealth, Edgar Villanueva discusses motivations for joining, focusing only on BAME staff. He says that yes, they want to change things. However, it’s also well paid, prestigious work with real power associated.

In the States, the majority of grants staff answering a Center for Effective Philanthropy survey had Masters degrees. Based on the evidence on LinkedIn (at least, those grants staff who haven’t deleted their pre-grant making pasts) I think their UK equivalents usually have Bachelors degrees, with some Masters. That makes sense: the degrees of the two countries are different. Also, there are more Foundations in the States which are huge, with a strong strategic direction where a relevant masters could help.

In the medical research field, peers with expert understanding to comment on the bid can sometimes be part of the assessment.

Bull and Steinberg in the UK report that there is ‘deep and widespread unease’ amongst grants officers about the lack of training for grantmakers, who ‘live by their wits and mostly learn on the job’. They identify a problem amongst traditional grantmakers, especially at Board level, who think training is unnecessary.

Reforming leftwing polemicist and longstanding foundation staffer Edgar Villanueva describes US foundations as working in ‘ivory towers’ with staff with limited experience of the issues, working to logic models ‘all too often not applicable to the work’.

In the UK, it’s undoubtedly true that grants staff very often have to cover many different areas of knowledge. In that context, it’s unsurprising that we are asked to avoid jargon.

Villanueva’s take on things is the most extreme take on their situation that I’ve seen and I wonder if he puts things as forcefully because he is campaigning for change. However, I once wrote a proposal to the National Lottery for Age Concern England, the then grants arm of Age Concern, in response to their request for ideas about delegating grant making. Our main argument was that, knowing the different Age Concerns and the work, the National Lottery had (at that point, in the late 90s) been funding the wrong proposals.

At the same time, even more so than their trustees, grants officers have seen projects going wrong and will have helpful views about what really works and what doesn’t.

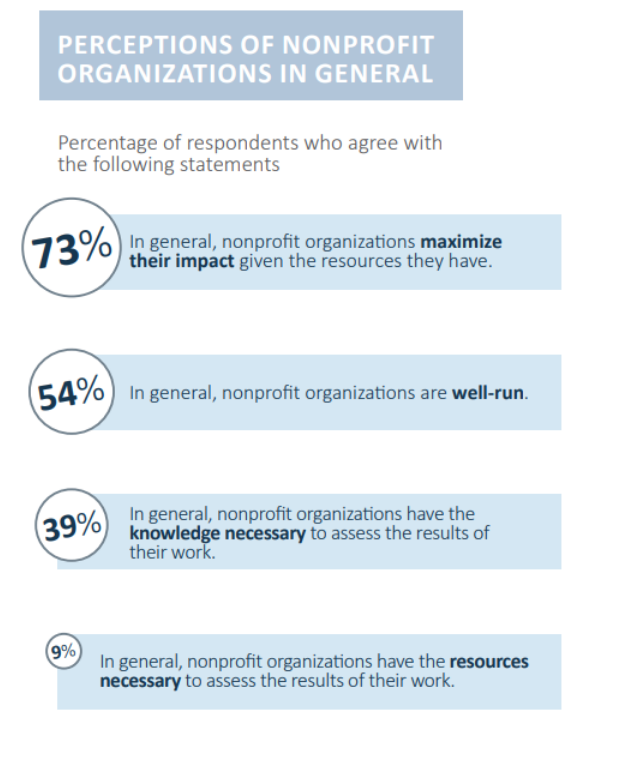

In the CEP survey, the grants staff had more discrete roles than their US counterparts (9% had a single issue area; 52% had “multiple issue areas that were interrelated”). Yet, whilst 85% thought they were aware of the challenges the grantees I work with face in achieving their goals, only 53% thought they had the knowledge necessary to help the grantees I work with assess the results of their work.

CEP survey results. (Note: a lot of respondents seemed to be more specialist and from big Foundations.)

‘It takes us as much time to process a bad proposal as it takes to process a good proposal.’ ‘What do we do with all this paper?! Sometimes I’m not even sure what we’re looking for.’ ‘I find it hard to get the info I want. Sometimes I am inundated with unnecessary and unrequested info…. At other times they just send what they want, not what I request.’ (Comments from grantmakers in the 2008 American report Drowning in Paperwork)

At a Fundraising Everywhere conference, trust fundraisers were asked to review applications for a trust. They were commonly surprised about how quickly they had to review things, compared with the time they had writing their applications.

In Bull and Steinberg’s UK book, a grants officer is quoted as saying during the pandemic (which was exceptional work) that ‘all I did was read applications and sleep’.

When I assessed for a capital funder, making grants often around the £10k level, I had maybe an hour to read and understand the four-page application, form an opinion on and write a half page summary and half page assessment report for each application. It was hard to get through when you’re tired, though when you know enough to do more on autopilot, that helps. I’ve read about people working faster than that.

David Burgess, who shortlists the applications for Fundraising Everywhere’s grant giving, makes the point that because of that tiredness, if an application doesn’t grab you in the first paragraph, it can be a challenge to keep the interest in it and it can be easy to start skim reading it. (Again, if you are very expert, you can conserve your resources better and have more ability to spot the key points.

(In passing: the following is an amusing exercise that will help you appreciate why assessors don’t necessarily spot everything in your proposal, despite working hard at it. Go on YouTube and search for “selective attention test”. It’s instructive about how the mind works! It will also help you appreciate how an expert will spot more than a beginner.)

In this context, behavioural psychologist Daniel Kahneman’s claim seems interesting, that the most effective thing you can do in influencing is to make it as easy as possible to say “yes”.

There’s mileage here, potentially. To quote Drowning in Paperwork: ‘Even though individual dealings between foundations and nonprofits may often be harmonious and supportive, the overall tenor of the relationship seems to be one of distrust and irritation on both sides. Funders find it difficult to get the “straight story” from nonprofit organizations, and often receive more information or different information than they want…[F]unders complain that they receive “the kitchen sink” from prospective grantees, who throw unsolicited materials into their grant application packet, just in case it might be of interest to the decision-makers.’

Themes of this web site will be: making things easy for the assessor; and making key points both memorable and to stand out. Even labelling what you send that is extra as clearly being extra (i.e., the assessor doesn’t HAVE to read it) minimizes irritation.

As Anheimer and Leat (2002) highlight, though, trusts respond to the demands on them differently. Some are more dynamic, others much less so – as you can see when you open a grants list and find nearly all the same grants are the same from year to year.

At each of the three main funders I assessed for, there were far too many applications for the money. So, I spent quite a bit of my time trying to find good, strong reasons to reject projects (as quickly as possible). Luke Fitzherbert at the Directory of Social Change used to start his trust fundraising training courses by getting people to pretend to be from a trust and to make grants to applicants. His observation was that the groups consistently started by rejecting applications, before sharing out the money between those who were left. My experience as a trainer (stealing his exercise!) is similar.

Villanueva and others have described having to sell the work to their trustees. There are different levels of delegate authority, but it is easy to imagine a middle ground like this. In my own assessments, I felt my duty was to make the work genuinely transparent to my grants panel, but I can see the strong temptation to want to sell a recommendation.

Picking up on Kahneman saying: make it easy to say “Yes”… One might check in with the grants officer assessing you: is there anything they need to make the report that they want to, to their trustees?

Villanueva describes having to speak very carefully to applicants because they would be parsing what he said for meaning as regards whether they’d get funding or not.

Don’t be shocked if you aren’t treated well by a trust, although good customer service is definitely the norm at the big trusts these days. One report criticizes trusts as ‘self righteous, arrogant and smug… discourteous… inaccessible… [appearing] arbitrary… [and] uncommunicative’. We are definitely moving away from the situation characterised in a (deliberately provocative) talk by former Foundation director David Carrington to the ACF a bit over 15 years ago. ‘[Giving a talk to grantees] my first [point] was that a foundation should “Do No Harm” to organisations that it supported – the comment drew a loud round of applause all round the hall. In discussion afterwards, I was surprised at the depth of the negative perceptions of funders, the many examples I was given of direct (and repeated) practice by funders that weakened in some way the organisations seeking funds – the processes and demands, attitudes and assumptions, funding conditions and focus on compliance and outputs. And the all too frequently reported and depressing examples given me of applicants (and grantees) having to bite their tongues in response to what they felt was a moral certainty and behaviour of some funders that was ‘unquestionable’; or having to twist the facts to fit the funder’s version of how the world should look – or to fit what ‘my Board’ will like or tolerate’.

Trusts are founded by the most generous rich people and attract good people who are motivated to help. The trust fundraisers I have met have been nice people and I don’t believe they would have metamorphosed into monsters by exposure to power. If you want my personal opinion as to why applicants have problems with trusts, it’s most likely to be because the trust staff are so busy. That said, applicants are extremely wary about criticising trusts (for reasons that will become clear later). So, it is unsurprising that poor practice can exist.

Edgar Villanueva touches on this in his book. The picture he paints is of hard-working staff trying to do a good job, but he cites occasional instances of capricious individuals, in a system with limited checks and balances. Bull and Steiberg are also clearly cross that, despite there being a lot of very talented and hard-working grants staff, they think there are poor staff who are nigh on untouchable.

As I said, I do think the big trusts are focusing more on customer service. I regularly talk to grants staff who seem to be trying to put me at ease and draw me out, which would rarely have happened back in the 1990s.

An interesting contrast in surveys… In the States, 88% of grants officers in the CEP survey said they thought ‘the grantees I work with feel comfortable approaching me if a problem arises’. That’s in stark contrast with a UK survey of fundraisers, where, a majority said that, if they had an issue, they wouldn’t tell the funder. How far is this a difference between the two countries and how far is it one of perception inside and outside?

The big foundations in the US can work a lot harder on engagement with grant recipients and that might explain the very marked difference.

I do also think there might sometimes be a bit of naivety on the part of trusts about how applicants see them. I sat in on a seminar where trusts were reviewing satisfaction surveys where grantees had told the trust what they thought about the customer service that the trust had provided to them. The personnel looked and spoke as if they were quite satisfied with the very high levels of approval they’d had. After this had been repeated by a few people, I had to pipe up, myself, to say that some of the reason for the high approval levels might be because they’d run the survey themselves. Applicants might not actually tell someone giving them money what they really thought, to their faces!

Trust staff usually want to be fair and reasonable, but they also take seriously the rules they have set up – meaning they may scrutinize you harder if you’re trying to play outside the system. This comment by consultant David Burgess, who has assessed, chimed with my own experience:

‘Take the proposal that arrived at one minute past the deadline. In this case we were lenient and read it (I’m not a monster!) but I was struck by how tarnished my perception of the proposal was by the fact it had arrived late. Starting from such a position meant the proposal was always going to have to work much harder to make it into the shortlist.

‘It’s likely that the person sent it before 5pm and that it just took a few minutes to come through. But the Grant Manager doesn’t know that.’

Source Drowning in Paperwork, Project Streamline, 2008

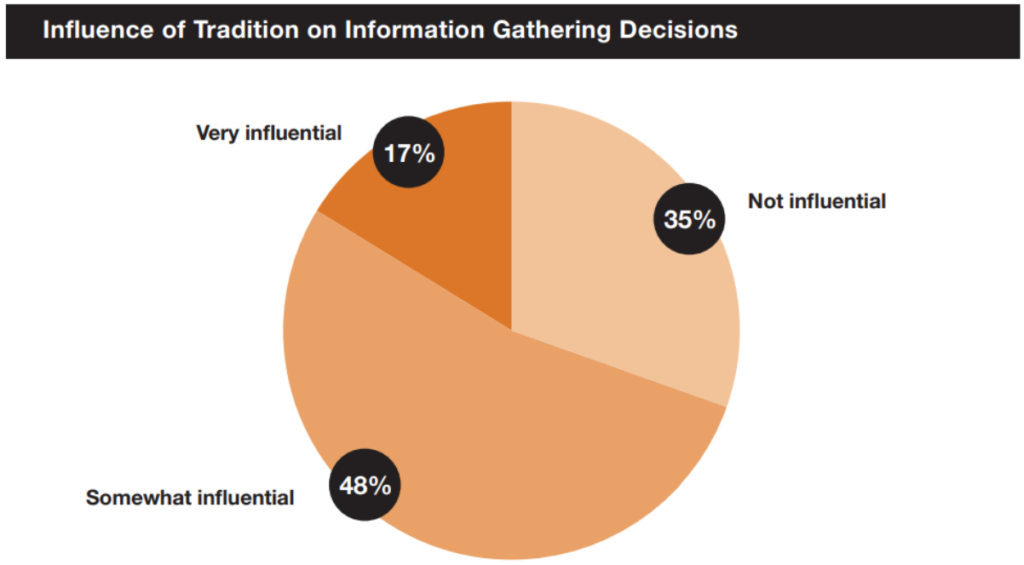

Project Streamline in the States found that tradition (we have always done it this way) is a significant driver for some foundations, particularly family foundations.

A central theme of Edgar Villanueva’s book, Decolonizing Wealth, is the difficulties that the big American Foundations he mixed with had in listening to the opinions of others. (In yet another polemic, he says: ‘They believe they know more than others what’s best for others. They make positive assumptions about their own abilities and negative assumptions about everyone else’s… They are plagued by mansplaining.’) I think this might be more of an issue in the States, where there are more major foundations that are proactively driving their own agendas more than reacting to the grant requests they receive.

Bull and Steinberg (2021) identified instances of arrogance toward applicants by grants staff in the UK, based on their own experience as grants officers and interviews for the book with other grants officers.

Psychologist Dacher Keltner found that exercising power encourages people to empathise less and see the world more in terms of their own point of view. So, one can see how that might happen. In the words of Gara LaMarche, former CEO of major foundations, ‘If you command [$3bn] surrounded by supplicants, you end up feeling a great deal smarter, wiser, funnier and probably handsomer than you did before.’

At the grant maker where I was most intimately involved, Age Concern England, we were very much kept in line by local Age Concerns, who were our grantees! So, it’s hard for me to comment. It’s very out of step with the comments in Trust and Foundation News, which treat the grantee very much as the expert.

I’ve done a webpage on “saying difficult things”, under the “General issues in proposals” sub-menu.

One of the big weaknesses of trying to discuss good practice in trust fundraising is that, as Bull and Steinberg hint, trusts are full of only lightly trained people independently finding their way to what they consider good practice, working to part time, unqualified boards that are incredibly insulated from mainstream practice. As people move around and there are a few membership bodies or discussion fora used by some of the big trusts, there is a degree of standardisation.

However, there’s a reason why there’s an adage, “If you understand one foundation, you understand one foundation”. People can be as idiosyncratic as they like.

However: there are pressures and a few legal constraints that encourage people to behave a certain way; the bigger ones, at least, often aren’t utterly isolated; and the closer you get to skilled, professional practice, the more predictions you can make.

That said, nothing will ever replace being a good researcher.

Chapman, T., The Strength of Weak Ties: How charitable trusts and foundations collectively contribute to civil society in North East England, Community Foundation serving Tyne & Wear and Northumberland, 2020 – Despite having a narrow focus, from a fundraiser’s perspective this might still be the single most informative report ever regarding the actual activity of trusts. It has really only three weaknesses: (i) the author doesn’t seem to realize it is heavily dominated by the views and activity of larger funders; (ii) occasional over-focus on issues of marginal interest to the vast majority of charities, such as funding that isn’t for grants; and (iii) the North East is a little different in having stronger structures for trusts from the region and nationally than most areas.

Trust and Foundation News, the newsletter of the Association of Charitable Foundations, accessible at the British Library and sometimes online. Read several issues, it gives a helpful picture of the preoccupations of larger institutional trusts. Again, it is a little distorting – in this case because it mainly exists to promote good practice, rather than to reflect what is going on.