Photo: Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash

This webpage is for trust fundraisers with three or more years’ experience. Beginners should USE THIS PAGE INSTEAD.

Photo: Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash

This webpage is for trust fundraisers with three or more years’ experience. Beginners should USE THIS PAGE INSTEAD.

In my nearly 30 years in the field, I’ve seen three main types of trust fundraising strategy:

All three of these are very respectable positions, in the right context and with the right person. The following will assume you do actually need a lot of strategy.

However, trust fundraisers tend to be do-ers who are under a lot of pressures. If you quickly write a strategy you don’t really believe in, that’s probably rubbish, just because it’s what your Senior management wanted from you, it’s going to be more of a nuisance than a help next year. So, I’d advise pushing back against strictures that get in the way of really helping yourself and your team. I’d also advise being pretty honest at this stage, so you get something “real world” out.

The DSC have published a book called Fundraising Strategy, written by Clare Routley (basically, a legacy fundraiser, but with a strong academic background and Richard Sved (basically a fundraising and management consultant / former Head of FR, who did five years’ background in trusts, or trusts and corporate and who has retained an involvement in the area since). It’s very profound and much of the rest of this webpage is framed as a discussion of the material.

I’m not sure Routley and Sved would agree with my characterisation of strategy as not always being useful – Richard Sved described it to me as something that should be “baked into” our practice. I’d certainly say you need to be pretty strategic and reflective. Otherwise, you can drift, whatever the situation.

It looks to be all things to all fundraisers, including heads of and as such, in my view it needs quite a lot of translation to our specific little niche, which is an outlier in some respects in the Fundraising Department. (Richard did mention to me that fundraisers in any discipline might see their area as having special qualities and I’m in no position to disagree.) As you’ll see, I also disagree with quite a bit of it – I’m guessing because it tries to make big general points based on a lot of academic research, without qualifying them for the very varied positions we trust fundraisers find ourselves in. However, it’s much too good to ignore, so I’ll treat it as something important to discuss, rather than something to follow.

At one charity, I spent three years with the purpose of my team fundamentally misaligned with that of Services. The underlying logic was that the charity wasn’t all about Services, it was about the organisation as a whole. Looking back now, I think that was absolutely right as a matter of strict logic and purity of motive, but stupid as regards the realities of working with another Department that you’re hugely reliant on.

Routley and Sved suggest starting your strategy with big questions, to provide focus (such as: “Can we increase income by 50%?”) That sounds like a good idea (whilst bearing in mind the need to manage expectations internally!) It adds impetus to the work.

The great management thinker Michael Porter distinguished between operational improvements – improving productivity, quality, and speed – and strategy. Both matter, but they aren’t the same. We inevitably want to achieve a lot of realistic and very important incremental improvements. However, management theorist Gary Hamel argues that ‘Strategy is revolution. Everything else is just tactics’. Do you have a place for revolution?

Over the years, I’ve instigated plenty of strategic changes: moving from just writing up applications to actively developing projects with Services; bringing in new resource to focus on groups of trusts we didn’t have the capacity to start working; introducing regional and then local approaches to a national charity; changing mailings from restricted to unrestricted funds; I’ve had a role as a first Lottery fundraiser.

On the other hand, many of these innovations have depended on unique opportunities at the individual charity. Even the things that some trust fundraisers are evangelical about, such as peer-to-peer contacts or getting new, innovative projects, may only work well in certain contexts. You may do a lot of work and find you just want to do more of the same with refinements – and that’s a perfectly respectable position to end up in.

We all know, though, that a growth strategy probably won’t be: do the same, on the same resources, for three more years. Gary Hamel’s landmark article for the Harvard Business Review is worth thinking about when we sit and consider: can we actually grow?: https://hbr.org/1996/07/strategy-as-revolution. To pick up his nine routes to profound change that could grow your income:

Another possible example… Tom Hall, Director of Global Philanthropy Services at UBS (an advisor to newer philanthropists) suggests asking philanthropists coming from a business background to invest in fundraising, because an RoI of, say, 6:1 is a powerful investment. He says you need to couch it in business language. A few trusts specifically exclude FR in their criteria and in nearly 30 years, I can’t remember seeing a successful pitch for FR income. Perhaps that’s because we don’t try it. However, it’s at least something to have in your back pocket with the right funder.

Trusts consultants Bill Bruty and Caroline Danks both argue that a trust fundraiser should be working about 50 trusts, but most will be trying to work with significantly more. The benefit to cutting back is clearly more individual work. That might mean taking on more staff, if you know the total number of available trusts is much higher. (In passing, as regards volume: it’s also worth considering the concept in Josh Kaufman’s The Personal MBA of “excessive performance load”. If you get people to try to do too much, their performance drops.)

To quote a recent HBR article on critical thinking: ‘A questioning approach to assumptions is particularly helpful when the stakes are high.’

However, Henry Mintzberg makes the crucial point that important strategic ideas rarely emerge in the abstract, they come from concrete realizations. He gives the example of the founder of Ikea, who came up with the flat pack when he couldn’t get a table in his car and a friend suggested taking off the legs. The chances are, the ideas you’ve personally introduced at a charity have come either from another charity, or they were something you tried out as a one-off and it worked. So, there are a few stages to the strategy development process:

As Michael Porter says, “value is destroyed if an activity is over-designed or under-designed for its use” (This is why this web site is only available to experienced trust fundraisers. If you don’t have a bedrock of common sense based on experience, you could waste SO much time implementing the ideas included!)

He also says that a good product is:

Despite everything I’ve said, if you cannot free up time to change strategy (or persuade your senior management team to fund more staff) then you cannot take on anything new. To quote Peter Drucker in an essay about productivity in knowledge and service work, ‘The first questions in increasing productivity have to be, “What is the task? What are we trying to accomplish? Why do it at all?” The easiest, but perhaps also the greatest, productivity gains in such work will come from defining the task and especially from eliminating what does not need to be done.’ (Later in the article, he adds defining performance as another key factor.)

My single greatest fear in creating this web site was that it would waste people’s time by encouraging them to take on over-complicated approaches. Everything in our work needs to occupy only its rightful place – and to be ruthlessly junked when it is less effective.

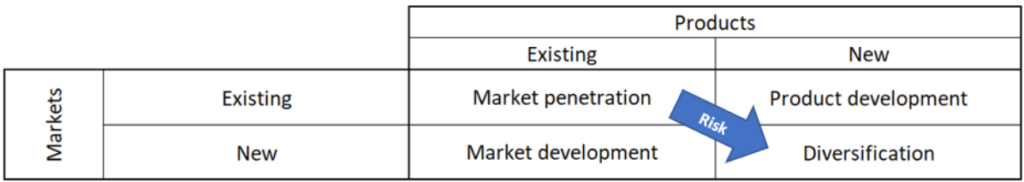

The third of the strategy tools in the video below – the Boston Matrix – is designed in good part to help you identify what to stop doing, which will enable you to do more of what you should.

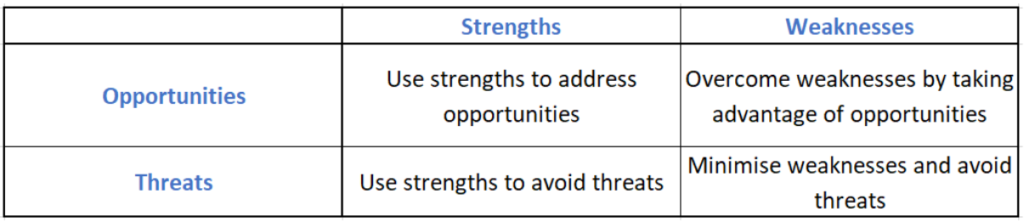

The following video looks at SWOT analyses, Kano analyses and Boston Matrices:

Routley and Sved make a few points about SWOTs that I’ll need include next time I redo the video:

This approach is in alignment with Porter’s points, above, about work being consistent and mutually reinforcing. It’s clearly a reason to have limited numbers of items in each of the four boxes in your SWOT analysis – if you have huge numbers, it gets harder to combine them.

(In passing: I once saw a facilitator try, and then struggle, to combine the elements as Routley and Sved suggest, in a strategy Away Day. It’s worth having a practice go in advance, with the SWOT elements that occur to you, if you’re going to lead a team session on this.)

If you want something more uplifting and inspirational than a SWOT, a SOAR analysis (which you can find online) will cover the same area but with a different slant. SOAR is also a bit more focused on involving others – i.e., Services, for us – trying to incorporate their ambitions.

Stop-start analysis: I’d personally say that, apart from a SWOT analysis, the most important thing you can do is to work out what you’re going to stop doing to make space for any new bright ideas. The number one thing that stops people improving strategically is just: doing more of the same. This is the main point, in practice of doing a Boston Matrix, but if you don’t do one of those then a “quick and dirty” alternative is just to have two boxes, one labelled “Start” and the other “Stop” and to write in each all the things you plan to introduce and finish in the strategy. Looking at the contents together quickly grounds your strategy back in the real world and gets you making the hard choices that a good strategy embodies.

People sometimes do a STEEPLE or similar analysis (looking at Social/Sociological, Technological, Economic, Environmental, Political, Legal and Ethical factors influencing the work) and Routley and Sved recommend this. However, after a few goes at STEEPLE-type analyses at different charities, it hasn’t made much difference for me in practice. That might be because I tend to look at external factors as I go along anyway, so when I come to strategising, any relevant issues will naturally come up in the SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats).

If you do want a go at such an analysis, there’s plenty of material about them online. Indeed, nfpSynergy wrote a 2018 report, that you might lift ideas from – the aptly named Look, nfpSynergy have done my PEST analysis for me! [“PEST” is a cut down version of the same thing and probably captures the most important four elements of STEEPLE.] They’ve updated it for the pandemic.

The most important thing about STEEPLE and similar tools are to get you “scenario planning” This is where you start looking at the world as it might be differently – considering how likely it is to change and if it did, what would be the consequences. .Whilst the kinds of things STEEPLE often throws up – changes to the economy, gradually evolving attitudes to volunteering, tech changes – might not actually affect your work, there are scenarios that could. What if your one key champion in Services left? What will the impact be of a new database that’s planned? What does Services’ new strategy mean to your work?

So, it’s worth thinking how the things that will impact on your world might change. PEST or STEEPLE might help you get into that mindset, but often the key changes are internal ones.

Routley and Sved also recommend a competitor analysis. Just sitting reading other charities’ reports and websites looking for trust fundraising ideas has never got me anywhere. They recommend another few ideas for information, such as Charity Almanacs and presentations. However, I think you’d be lucky for that to work for trust fundraisers. The whole point of doing this website is that the published information tends to be incredibly basic and we’re all forced to sit through endless highly repetitive presentations, looking for “nuggets” of useful information.

On the other hand, a possible idea that Routley and Sved suggest is speaking directly to competitors. Trust fundraisers are a friendly and helpful bunch, if you ring your “competitors” on the phone for a chat. If you’ve only worked in one or two charities, maybe somewhere that believes there’s One True Way to fundraise, it’s worth knowing: there definitely is a variety of good practice out there. So, at the least, it’s worth speaking to others if you’ve only ever fundraised at a couple of places. If you’re more experienced but you rang half a dozen comparable trusts teams about strategy, I’d still be very surprised if you didn’t learn something useful during the course of the conversations.

Routley and Sved recommending finding “best practice exemplars”. Good luck on working out who they are, for your charity, in our field of work! Trust fundraisers rarely pop up at awards. You could try approaching some consultants, perhaps. It would be unfair to the charities in question for me to name anyone I think is an exemplar on a web site that will (hopefully) be viewed by large numbers of trust fundraisers. You could try engaging the people, like me, who’ve positioned themselves as knowing a lot – most of us seem prepared to give a bit of time, at least.

Routley and Sved make the very good point that you’re looking for key principles that might apply to your work, rather than trying to import other people’s approaches wholesale. This is a basic principle of learning: it’s much more effective to understand “Why?” than to be able to slavishly copy someone’s ideas. (If you want to know what’s kept me awake at night about this website, it’s that people might mess up their existing practice by implementing my wacky ideas in a naive way, rather than being challenged, made to think and then building on their own experience. It’s why I’ve tried to bar less experienced fundraisers from looking at it.)

All of the above is just about having ideas for strategies. Once you’ve got the ideas, you need to do the analysis and then use the strategy.

As Routley and Sved say in their book on FR strategy, good work is grounded in solid research. Once you have your first thoughts on strategy, I recommend you watch the video I did on using Excel for analysis and download the accompanying example spreadsheet. Every decent strategy I’ve ever done has seemed to involve intensive number crunching based on past data.

Another Routley and Sved suggestion is market research into donors. As we spend a considerable part of our time doing that already, the only point I’ll make about it is one that’s already in the Research section…

If you’re having problems with the judgement calls you have to make when researching donors, it’s worth spending some time “reverse researching” your existing funders. That means: spending at least half a day with a list of the funders, looking up their materials and seeing what patterns you can spot. For example, doing that at my current charity I found:

I’d be surprised if you found exactly the same. That’s why you need to do it yourself, rather than taking notes about “what a good prospect looks like”, based on the above bullet points.

Routley and Sved envisage people doing market research by ringing groups of donors. I’d heard of other charities doing this with trusts and recommending it. I’ve only had a couple of goes at it myself, which did more to give a few tips about individual relationships than to ground our work in better understanding. I’ve had two problems achieving deep learning from such market research:

Routley and Sved recommend benchmarking with your competitors. There are benchmarks produced by, e.g., LarkOwl (who do both trust fundraising and benchmarking) use about 10:1, though it might actually vary between about 5:1 and 15:1 depending on the circumstances. You only need to wordsearch benchmarking in trust special interest group chat sites to realize the skepticism that exists around it. I did a four week contract where my work had a RoI of 1:800! That doesn’t make me the world’s greatest fundraiser (though it was good work). It was just about the context. However, it would be to throw the baby out with the bathwater to completely reject benchmarks.

It can be easy to get a benchmark and feel, “Er… so, what do I do now?” All it really tells you is that someone else is getting different results. All the same, it can be an interesting challenge to you.

Benchmarking against your different predecessors over the years can be very useful, though, because you can work out how they worked and compare it with what you do.

Routley and Sved make the good point that you ought to contextualise how you differ from the benchmark, so that no one senior in your charity uses the benchmark as a stick to beat you with. You can only do this so far, of course, because you don’t really know the differences between the charities.

Routley and Sved suggest you set SMART objectives. Given that the audience for this site is experienced trust fundraisers I won’t explain “SMART” (though I do comment on it in the webpage on the Monitoring and Evaluation section of a proposal).

Routley and Sved spend a lot of time discussing using Ansoff’s matrix. In our context, new “products” would I think be things like services, or very different presentations of them and new markets would be new donors.

A lot of what they say about segmentation was developed for what, to us, would be mass markets. However, it’s still a useful lens for making some points:

Market penetration I’ve found in my current charity a situation I’d suspected in others: that the numerically “big” markets (the smaller trusts) were under-explored and there was more money out there if we put more staff time in. However, the Return on Investment can go down, as you can end up looking at quite targeted (i.e., not very efficient) work to secure smaller (not more than £10k) donations, in a part of trust fundraising that has lower RoIs already. If you’re bringing in less experienced staff to penetrate that market further (my experience) it can take up time for more experienced staff by way of support, which is time they then aren’t putting into fundraising for bigger grants. So, budgeting for such a new strategic approach needs to be done very carefully. Clearly, though, as trust fundraising functions grow, “hiving off” smaller trusts into a dedicated post is a natural part of the process.

Diversification I think the “greater risk” arrow is very apt here! A number of times I’ve had my Head of suggest I should be excited that Services are developing something in a different field of work, that would enable me to attract very different funders. Well… Let’s assume the new work is great and you’re capable of getting the proposal to reflect that. I’ve seen two issues:

“New”?

Trust fundraising is a field where it’s easy to innovate in small, low cost ways. As such, Mintzberg’s view that the best “new” strategy ideas are the ones you’ve already tried, a bit, is very relevant. It’s all the more useful to know your charity’s history and to keep in touch with your predecessors in post. However, because we send smaller numbers of applications and often all we know is whether the money came in, there may still be considerable risks.

Segmentation

When looking at new posts, it’s worth playing with the projections to see what changes if you change the segmentation. A number of times, I’ve found that a post that doesn’t work financially with one set of grant sizes does then work if you change the segmentations a bit (and would still work with the caliber of post-holder you can expect to attract for the salary). So for example, I had a post that had too low a RoI if it included many approaches for less than £5k worked if I introduced a minimum income cut-off. Another similar-ish role worked better if I added in responsibilities for seeking grants a bit over £10k.

Mintzberg, already mentioned a couple of times, is a key thinker about business “in the real world” – it seems to be his mission to get us to “come off it”. He suggests five ways to look at things, corresponding to 5Ps. I’ve never tried this for a strategy, but there’s some sense to his idea. Mintzberg says they are considerations:

He says, look at things considering the following:

Planning: strategy needs to be developed in advance and with purpose.

Ploy: strategy is a means of outsmarting the competition.

Pattern: What do we naturally do? What worked in the past may produce success in the future.

Position: how we relate to our environment. There’s a lot in business about what you can do to make its products unique in the marketplace, perhaps that needs modifying for us to: how do we best fit our particular marketplace, with a good USP as one factor

Perspective: emphasizes the substantial influence that organizational culture and collective thinking can have on strategic decision making. So for example: what’s your team’s and your department’s attitude towards risk taking?

Routley and Sved recognise that strategy needs to live in the real world where not everyone automatically agrees or will go along. However, their main audiences aren’t junior figures like ourselves, who need to influence more senior figures in another department to get very far. As such, many trust fundraisers will find the techniques presented in their book rather under-powered. They present a lot fewer ideas than in the webpages on this site about internal analysis, presentation, persuasion, negotiation, politics, problem solving and more. However, I liked one point they made:

Get buy-in from key stakeholders They make the good point that, if you can present the strategy as not yet finished and get senior stakeholders to amend things (and one might add, be publicly seen to have been part of the process), they’re more likely to own the results. This wouldn’t necessarily have worked in the charity where I worked for three years where Fundraising and Services had been at war over trust fundraising before I arrived and where the only way I found to keep the peace for three years was to hide from each side the strategic intentions of the other. However, where the differences are small enough, it sounds a great idea. It could be quite a high stakes move, though, in charities where the differences in priorities / philosophy are considerable. So, it’s worth testing and preparing the round carefully first.

Change management techniques As described in the “getting things done” webpage on this site, the worst case scenario is that you have to start working on a “change management” basis. Routley and Sved run briefly through Kotter’s change management approach. Perusing the literature on change management will highlight that even powerful, senior staff find it difficult to make major change stick and that change management is the “high power, hard work, long term” approach they are recommended to use, to drive real change if they have to. I’ll discuss it briefly below, though, because you can probably use it with your own team if you manage trust fundraisers.

Trust fundraisers can feel a lot of pressure, for example towards productivity. If things aren’t quick and easy to introduce, it can be challenging to make changes in such a situation:

Look at past SWOT analyses {see above) that your team has done. Do the biggest ideas in the Opportunities box look like “nice things we’ll do some day”, with hindsight? If so, where did the inertia come from?

You’ll have to actively drive any change – that’s your job when you lead on strategy. You’ll also have to think how to really make space for that important new idea. Is it through additional staff? Can you realistically budget to take a hit on income this year? Can you give the project to a reliable volunteer? Can you/your staff stake out some time specifically for it?

As a manager, people won’t necessarily tell you why they aren’t adopting your whizz bang revolutionary new idea. At one charity, I spent a year trying to push a new, more contacts-driven, strategy, with only limited success. The minimum would get done, but that was all. It wasn’t until their exit interview that one member of staff admitted the truth: they weren’t sure if a contacts strategy would work, but they knew that business as usual did. It was stressful enough trying to hit target. Doing it in an experimental way was a step too far.

It’s more an issue in your area than some others. You probably aren’t “swapping out” a mailing, or an event, for a new, more experimental version. Faced with potential mutiny by his Conquistadors, Cortes sank his boats, forcing his crews to have to go out and conquer Mexico. That’s kind of what the Events Manager does when they say, “We’ll run this new event instead.” That’s not an option open to you in the blur of proposals and you need to act in a definitive way to make change happen in that context.

You may be in a change management situation. The key figure in this area is John Kotter, whose key book is Leading Change. There are lots of summaries of his ideas online, e.g. at Mind Tools and similar sites. The fundamentals are:

Kotter argues that the key reasons change initiatives fail are: (1) there’s no real sense of urgency; and (2) people think it’s over after the “quick wins” and slack off, when actually you may not even be halfway to lasting change, yet.

Another list from Kotter (that I found in a book on working in volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous (VUCA) environments) is:

In my own experience, perhaps the most important thing about creating more difficult changes might be: when you’re getting somewhere, you haven’t won, you’re only a small way into the change and you need to find ways to keep it going. Kotter’s the expert, though – read his work.

The biggest single grant I ever had any involvement in (£14m; I only did a small part of it, btw) didn’t come from the funder. It came from two large nationals coming together and going direct to the funder and asking, “This is a huge issue. Would you consider something huge in response?” If you’re never very ambitious, you’ll never get big results.

At the same time, ambition can involve extra risks. In that example, the two leaders of the charities and the fundraisers supporting them put some ordinary work to one side for some time to make this pitch. It was pretty unlikely, if you were an outsider, that they’d get anywhere – the grant was one of the biggest that the funder had ever given. So, you need to decide on balance – how much time and opportunity do you put into the big asks?

However, if you never go big, the possibility of surpassing your targets significantly is completely out of your hands.

Routley and Sved wrote Fundraising Strategy, published by DSC. It’s pretty heavy-going – if you think a website of 100 often quite long pages is a lot, try reading a dense, 200-page book on just one aspect! However, it’s fairly rigorous and profound. It took me about three hours to quickly gut it for the above and I already knew quite a bit of the material. Much as I think it needs translation to our setting, I’m sure I’ll re-read it in the coming years.

It’s too specialist for this site, but: if things have got chaotic, again, there’s a lot out there that you can read that will help. One recommended book is Change: How Organizations Achieve Hard-to-Imagine Results in Uncertain and Volatile Times by John P. Kotter, Vanessa Akhtar and Gaurav Gupta.