Photos: Matthew Henry and (insert) Thought Catalog, on Burst

This page was written for very experienced people. I wrote this site assuming that beginners wouldn’t calculate their own targets – but for beginners this page may help.

Photos: Matthew Henry and (insert) Thought Catalog, on Burst

This page was written for very experienced people. I wrote this site assuming that beginners wouldn’t calculate their own targets – but for beginners this page may help.

I’m not going to go into great detail about this area, as there’s a great target setting course run by Bill Bruty, which refined the way I like to do it. If I were to give a thorough account, it would basically replicate his course, which would be a bit unethical.

As a result, what follows is really “get you by” instructions to put together reasonable targets.

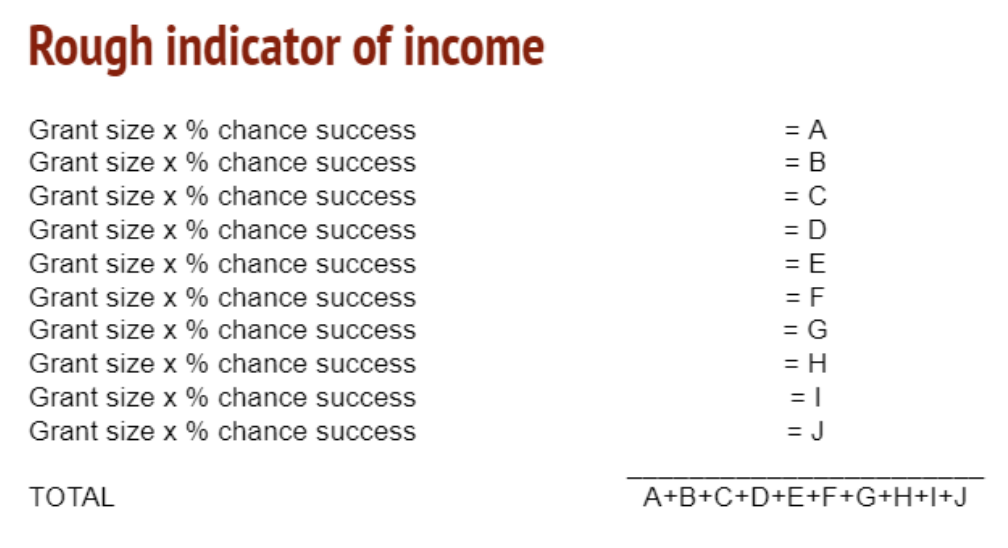

Targets are normally based on aggregating something called “expectation values”, which is the chance of getting a grant, multiplied by the value if you got it:

So, how do you calculate those two figures?

You can use that approach for the different sub-headings in your budget (big and small trusts, different Services areas, etc) and especially for the budget as a whole.

The smaller the number of funders involved, the more “rough and ready” and the less reliable this approach becomes.

Likewise, it doesn’t deal very well with huge applications. You’ll have to do something different for them. I personally discuss them with my manager and we agree on something that works for the Department / my Trustees. Bill bruty has some good ideas, which I’ll leave him to explain to you.

I have been handed this down on many occasions. It’s simply not a reflection of the real world though and just reflects organisational convenience:

If I get a target like that, it doesn’t necessarily mean that we urgently need to raise that or the charity is in trouble. From a Senior Fundraising Manager perspective, there are various sources of income and variations might balance out more than that.

My priority is my internal relationships. I’ve been given an unrealistic target and whilst I’ll do my best, they need to know that and be okay with me. (If you’re any good, you’re not getting fired over a missed target. However, you do want your managers to think well of you.)

My response is therefore:

As the year goes on, I do a decent reforecast and keep speaking to my manager about the level of realism of hitting the target.

As mentioned above, Bill Bruty does a great course on this, which goes into greater depth than I have here. I thoroughly recommend it.