Photos: Hush Naidoo on Unsplash

The material on this webpage is for people with at least three years’ trust fundraising experience.

Photos: Hush Naidoo on Unsplash

The material on this webpage is for people with at least three years’ trust fundraising experience.

Very large applications create three new challenges for trust fundraising bid writing:

Another consideration, partnerships, is dealt with under another menu (as it’s not theoretically a “big project” issue)

A particular role someone needs to have with huge applications is to project manage the work needed to assemble the application. It is more work than it sounds – I’ve project managed multi million pound applications with partnerships and got to the afternoon before I’ve had time to do any work other than checking in, briefing people and troubleshooting the bid writing process.

It may be worth briefly doing a matrix for very complex applications, that lays out who’s:

A realistic bid writing process is one where those people are going to do their bit and you have strategies for dealing with problems you’ll encounter.

Along with who and what, when is often an absolutely central question. If I had one single criticism of charities handling major projects, it’s that they struggle with the timings. They can take far too long to really get everyone going and often don’t bring the senior people along, who start making big suggestions at a stage that is too late for them to be incorporated sensibly.

It’s well worth critical pathing a big, complex project. In a nutshell, this involves putting the timings of everyone’s tasks on a GANTT chart and identifying pinch points, when too many demands are being made, when people are away on holiday, there’s time for approvals, including at committees and other “reality checks”. Then, you identify the critical points on which the timeline for completing the application depends. If there are too many close to each other, or they sit with people you can’t rely on, you’ll need to adjust. Then, as someone project manages the bid process, they’ll need to pay particular attention to ensuring the critical path is met.

Getting clarity about the basic idea earlier rather than later, then clarity about the next biggest ideas, and so on – and communicating these – will help.

In the last days of a project, if there can be no more changes to the basic model, you’ll do much better. As you develop everything, the work becomes more and more interconnected. So, the bigger the change is and the later it comes, the more likely it is to leave your application with internal contradictions.

Allied to that, you need to go through each section of the project and application and spot the issues: We need the project to be tweaked in this way to reflect this criterion or this major focus of the assessment, but that means that the need will be a bit different, so will the project and the description of who we are as an organisation, and so on. Going through everything in advance and spotting the dangers – and going back through it occasionally – will put you more in control of the process.

It’s good to let people KNOW they’re on the critical path and if they don’t deliver it could throw things, even if they are weeks away from the due date. No one likes thinking that everyone might think they messed everyone’s work up.

If you can manufacture smaller, earlier, intermediate deadlines, that will give you more control over the bid writing process – it becomes harder for people to try and put their bid off because, hey, the application isn’t due for weeks yet, what’s all the fuss?

An import aim is to find a way to get as much going as possible. Big projects can involve a lot of interdependent things, meaning it can be easy for things to get held up while you wait on one development or decision. There’s a skills to overcoming these bottlenecks where you can.

A key challenge in any large application is ensuring that senior staff are engaged at the right stages. If you just try and bring them in at the end, there’s a decent chance they’ll endanger your application, either by telling you internal realities you couldn’t know at your level, or by wanting to put in their big picture ideas that’s actually inappropriate for the project model or don’t tally with the development work. The way to avoid this is to find a way to engage them in stages – getting an initial “in principle” agreement after a chat with them about the idea or a short concept note, then engaging them on anything major as you go along, so that at the end they agree your project, rather than agreeing it with unworkable changes.

Critical paths are easy to understand, put together and even get agreement to, but vulnerable in that, if you’ve built a path to submission exactly on the date, you’ve just built in a whole load of points where the application MIGHT fall down. If you can get your organisation to go with the idea, you could use a “value chain analysis”. With that approach, you give people the shortest reasonable amounts of time (saving some time in case things go awry) and monitor how much of the saved bank of time you’re actually losing through delays. It’s potentially more robust. However, it’s harder to manage and work with people on. I’d start with critical paths and graduate to value chains if you think you can make them stick.

One point that’s not obviously on the critical path but that can matter a lot: the budget. You may not need exact figures until late on, but you DO need to know that it’s all affordable

At the same time do watch out for unrealistic pronouncements. You can discredit yourself a bit internally by saying X will be ready by date Y and it isn’t.

If time looks very short, start getting time in the key people’s diaries – even if you don’t know what it’s for, yet. If you try and fix up a meeting with everyone at the last minute, it probably won’t be possible, so having the opportunities for people to decide together means you can respond. I actually tell people “This is a meeting BECAUSE time is so short, I’m not 100% sure we’ll need it in the event, btu it’s there because, if we did need it, not having the chance to talk would sink the application”.

This is a massive issue, that is covered in another menu on this website.

I’ve seen multi million pound projects introduced at charities that would never have been dreamt of by the organisation if the funder’s money hadn’t been on offer. The normal rules with small projects are: you do what’s in the strategy and what Services actually want to deliver. When there’s a lot more money on offer, that becomes much more flexible, internally.

Creativity becomes possible. This is one reason you really need to understand the issues of your service users, the aims of services staff, service models, what works in project management terms. Then, you can actively contribute to the best fit project. However, if you aren’t capable of that kind of thinking, you probably want to brief a responsible senior manager of staff well on the funding opportunity. They often have very good skills in this area and you can throw it over to them.

It’s best to get things grounded in the real world – checking practice toolkits, speaking to front line staff, getting some service user involvement done if that’s realistic in the time / organisational culture (service users have expertise by experience that complements the technical expertise of staff – at their best, projects can be “co-created” with input from well informed, confident service users who have time. Okay – I’m getting off my hobby horse, now!) Senior staff can be very brilliant, often know what their staff want and are afforded more flexibility than those further down the tree, but they take decisions relatively quickly based on basic principles and it may be worth looking into the nitty gritty and suggesting tweaks/extra development, armed with facts.

Anyway – with any new project, what you’re always looking for is a project that is squarely within the interests of the trust, squarely within the interests of the charity and is good (ideally, best) practice. With small opportunities, you’re often thinking in terms of how to write things so that they are (true but) appeal to the funder. With very big projects, where you’ll have assessors who will pride themselves on peeling away some of the packaging, I’d focus more on getting the actual detail of the intervention, client group, etc, right.

It’s worth rewatching the video on “Tweaking applications for funders ”. That’s what you’ll often do for the biggest applications – but possibly, writ large.

You need to think about the overall structure and language, especially if there are a number of people writing the application (or you’ll need the capacity and time before the due date to rewrite their work!) It’s MUCH easier to write a two or four page application in this sense than a 20+ page one.

As psychologist Steven Pinker argues in his book The Sense of Style, a challenge people have is that when they’re thinking about something, they think it in the context of lots of other thoughts, but when its in writing it sits in isolation and it may not make anywhere near as much sense as it did to the writer. That is especially true for long proposals. You have to keep the reader aware of the context and not assume they’ll know things you haven’t mentioned yet or remember what you said five pages ago. It’s a completely different experience to read something for the nth time that you’ve been working on for weeks, versus having to canter through everything in an hour to assess it against lots of criteria.

The key issues are structure and internal signposting.

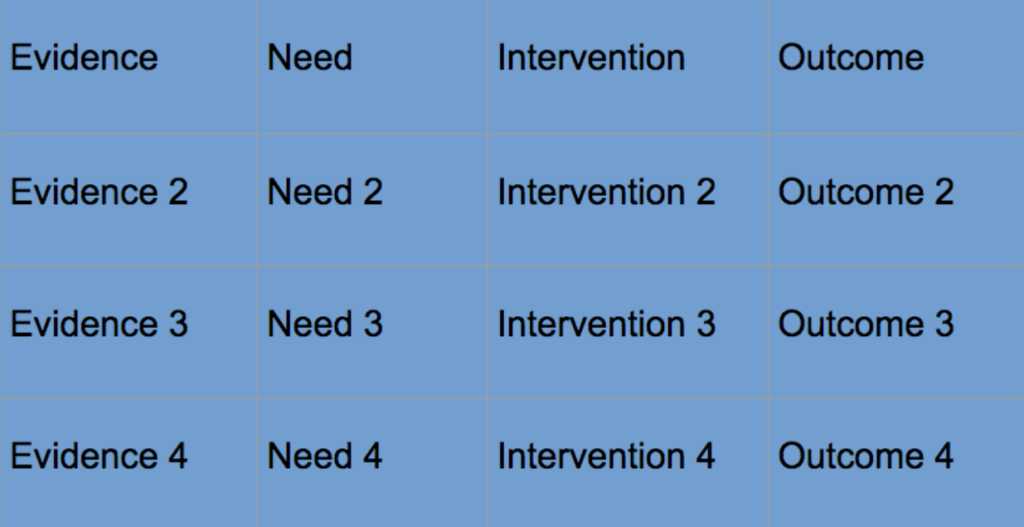

It’s worth considering a consistent structure across the application. When you’re in the middle of a big application, it’s easy to lose where you are. So for example, doing everything in the same order:

It’s worth considering also how to ensure you use consistent sub-headings and consistent ways of referring to things. The more “internal signposting” you have in an application, the better.

As you go from a few lines about something to a few paragraphs, you also need to think about how your writing is driving at something. Is it always clear where you’re going? If the assessor doesn’t know where they are in what’s effectively an extended argument, they may not see the point of what you’re saying.

I would advise you to map things out roughly. It also helps to use the fundeer’s own points to cover as headers, or at least to incorporate the working.

Everyone also needs to know what’s in related boxes on the form before they write. Things written in isolation may not relate and may need rewriting. A long application that evolves a lot in the writing will probably be a mess, or at least inefficient because so much needs redoing.

Applications are very hard to write where you aren’t clear, relatively early on, about the basics of the project. The detail you’re working out is subordinate to the big ideas, so those need to be clear. if they change, what’s been written will have been written for a different context.