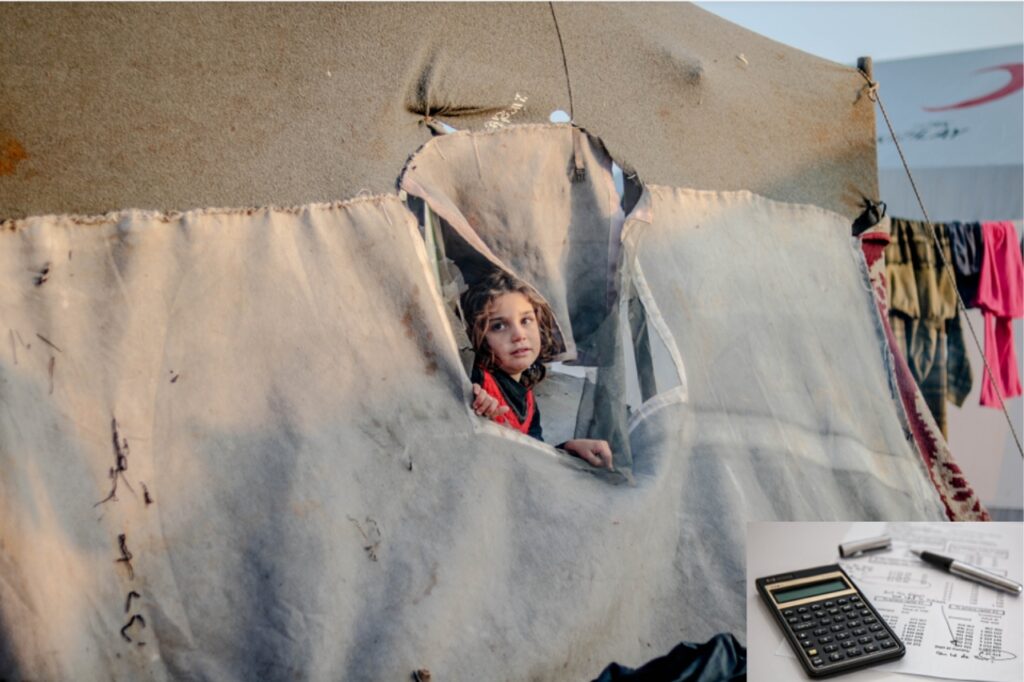

Photos: Ahmed Akacha and (insert) Pixabay, on Pexels

This area of the site was written for very experienced trust fundraisers.

Photos: Ahmed Akacha and (insert) Pixabay, on Pexels

This area of the site was written for very experienced trust fundraisers.

This is a subset of the wider question: who does the development work on a project? There’s a whole sub-menu on developing projects, because it’s not easy in practice.

If nothing else, you ought to be able to cut up a budget produced by Services into smaller parts, but sometimes you just have to budget things yourself.

An additional consideration when deciding: can you budget this? The more ownership you take, the more ownership will stay in FR for reports and regarding the auditor. For example, because I’m a kind and skilled man, I’ve done the budgeting on £500k Lottery projects with lots of pro rata contributions to staff salaries. When the reports come round, I have to construct the reports from the actuals myself and I have the conversations with the auditors. (It would be easier if every penny of funding came from the one account, but it doesn’t.) That’s time I’m not spending writing applications towards my target.

Your job is to approach funder for a certain amount of money for something. If you don’t know how much things cost, you cannot decide what to include or leave out of the project. That means you can’t accurately write most of the application – the project section nor, by extension, the outcomes nor, by extension, the need. Nor the description of an organisation that is highly suited to that project, expertise delivering whatever it is and so on.

The further out from the are you know, the more important it is to get the rough model, with rough costs. I once had to quickly put together a £5m over five years national programme in a new area of work for the charity. Very quick, back of the envelope calculations, indicated we might get 15-20 sites. However when, a week and a half in, I’d finally got all the experts together with the relevant Director, it was clear there were so many key needs to address that we’d only be able to afford five sites.

Consequences:

Senior staff quite often budget “top down” – “We can apply for £250k, which is £80k a year. Two Coordinators would be about £55k, plus £10k running costs leaves £15k on costs which is about 20% of the total.” This is very useful to keep the conversation going, but “top down” budgets can easily make too many assumptions. So, it’s worth just checking in the meeting would they be okay if, when we do the detailed costs, it came at 1.5 staff instead of 2?

Another good way to do things at speed, if you swot up on the existing budgets well, is to talk by analogy: “When we applied for a new Education Coordinator for the Bloggs Trust, the costs over three years came out at £50k a year. We could maybe get a full post, plus one that is a half time or three day a week post for £80k a year.”

There really is no logical reason not to have the direct costs and salaries budgets for all the services you fundraise for. Finance will just have them in a folder, somewhere. They’re probably well broken down, because otherwise how would the service team get their work approved? There should be reforecast spreadsheets that keep things up to date.

I’ve been at charities where these things are shared with the Trusts team. You’re a grown up and should be perfectly capable of keeping them confidential, for the minority of costs where confidentiality is important. They’re extremely useful.

My editor, Robyn McAlister, made a very good point when reading the draft. Your budget should tell the same story as your application. There shouldn’t be anything in the budget that the funder doesn’t already have some context on – e.g. a staff post that’s never been mentioned. Budgets aren’t the place for surprises!

Suppose you end up having to work on the budget. We’ll assume you know clearly what your project is (otherwise you’re in trouble trying to budget it in detail). Where do you get the costs from?

If it’s a complex project and you aren’t clear what the line items of the budget are likely to be, it might be worth doing a “work breakdown structure”, which is just a structured way of getting all the tasks down on paper. It may well be clear you can spot (or at least discuss or research) what the costs are likely to be when you look into each item.

You need a decent specification before you can get accurate costs for a line item. For example, there’s a big difference in both abilities and costs between a psychologist and a counsellor, or an advice worker and a worker with Social Worker qualifications.

It’s clearly a good reason to have easy access, with indexing, both to all your team’s past proposals and all Services’ budgets and reforecasts.

Online desk research takes time but will get you a surprisingly long way. There are plenty of sample/model budgets kicking around. If you go on recruitment sites, you can find example salaries for similar work. (Probably best tell your co-workers what you’re doing, if they sit where they can see your screen…) It’s also important in the case of salaries that you also reflect the internal salary scales, which are normally detailed in a remuneration policy. If you really don’t think you could recruit to the post on the internal salary scale (as is sometimes the case) you’ll have to either consider changing the responsibilities of the post to make it work or argue for a premium for the post.

However, it’s very important that the Services staff are involved, even if you have to do some leg work. Whether they want a high end or low-end laptop, or a health advice worker, is their decision. You might be able to make project development easier, but that doesn’t substitute for the expertise to take the big decisions. Plus, they need to actually own the project!

When you start out, you’ll need an idea of what the budget might look like, to enable the evaluation and to get everyone to agree it’s worth fundraising for the project. You may be able to use data from previous projects to build an estimate of costs for the current project. For example, look at similar, or analogous, items in the previous project, scale up or down and add inflation.

Alternatively, you can identify the big components and cost them roughly. For example an advice project is probably mainly staffing, plus office costs (which you can do as a proportion of the costs based on other projects or a proportion of the costs of the specific office) plus overheads, plus maybe a few smaller costs (e.g., Matrix IAG accreditation, or access to a database).

There are two sides to this:

An attached spreadsheet demonstrates several techniques I find useful:

Like every part of bid development, having the right budget is about reconciling the charity wants with what the funder wants. If Services propose a project for people with Profound and Multiple Learning Disabilities working many hours a week with each individual at a cost of £20k p.a. per head and you don’t think that would fly, you might about a service that is less days a week (or possibly less focus on PMLD, if that does actually fit the remit and goals of the individual service).

There comes a point where this is mission creep/just chasing money, but before that there’s a region where you’re just trying to make things fit. It’s the difference between understanding the funder, the service and the field of work on the one hand, and just being able to write something up on the other. A very good trust fundraiser has the wider skill set.

We’re usually targeted on income in during the Financial Year (occasionally on income FOR the FY, which is a lot meaner!) However, with new projects there’s a danger that, even if you get the grant within the FY, it won’t count towards that year because there’s no actual expenditure in the year. This is due to a process called “accruals” – the money is “accrued” into next year, even if it technically sits in your account before then.

Common causes of this are:

What can you do to mitigate this risk? (Don’t worry – some of these are relevant to budgeting!)