Table of contents

Case studies and storytelling

Photos: Logan Weaver and (insert) LinkedIn Sales Navigator, on Unsplash

The material on this webpage is currently for people with at least three years’ trust fundraising experience.

Drawing from journalism

There are various useful tips for proposal writers in journalism. I used to have a trust fundraiser who worked for me who came from a journalistic background and his proposals were clear and engaging, concrete with good written pictures of what was going on, both for the service user and within the project itself. (As a newshound, he was also great with deadlines and not afraid to work hard and efficiently to meet them!) As well as photojournalistic tips such as a compelling first paragraph and telling stories with your photos (described in another tab in this menu) he completely “got” the role of stories in trust fundraising.

Stories in trust fundraising

In the States there’s a whole book themed around storytelling for grant writers, called Storytelling for Grantseekers: a Guide to Nonprofit Fundraising, by Cheryl A Clarke. I think she’s onto something, though her book is more about describing standard techniques by drawing analogies with storytelling (which some may find useful – and her book is well written) than digging deeply into stories and their power.

People will sometimes try to “sell” you storytelling techniques for fundraising (e.g., Ken Burnett in his “thinkpiece” book Storytelling can change the world). They say that stories have been with us since the dawn of humankind and so they’re hardwired into our brains. Whatever the actual evidence behind this, when you start noticing it, stories do seem to have a pull with people and to be a clear way of showing some things.

There are three excellent uses for stories in our field:

-

Increased clarity when you describe the project

One technique that my ex-journalist bid writer did very well was to describe the service by giving a sense of what it is like for the individual going through the process. You may find, like he did in his time with me, that it increases the clarity. It also arguably increases the power a bit.

So for example, you could write the project description by saying:

Music therapy works for children with severe cognitive impairments to engage and to develop valuable skills, such as sensorimotor training, Speech and language training and Cognitive training.

A storytelling approach might say:

When a child starts with music therapy they are probably withdrawn and confused. However, they still have innate senses of music and rhythm. Our music therapist works with that. They start to recognise and respond to rhythms and music. As they develop this musical “conversation” the therapist is able to encourage them to develop physical skills as they bang a drum. they can encourage them to phrase things and practice their speech as they repeat back in song. They can learn patterns and counting in the same way. their latent musical abilities make the process more fun, absorbing and easier.

I took a lot longer the second time (I’m not a former journalist!) – but hopefully it “meant” more and was a little fascinating. (That was certainly my experience at a children’s hospice!)

2. Moments of persuasion in extended conversations

One of the doyens of major donor-style fundraising, Rob Woods, advises in his book The Fundraiser who Wanted More, that people build a notebook of stories they come across – so that they have those stories to hand and crucially so they go in the memory for when they’re needed.

Rob is a big proponent of the power of stories full stop, but I think there’s one good one potential use for them with funders.

In their excellent, research-based book, Insight Selling: Surprising Research on What Sales Winners Do Differently, Mike Schultz and John E Doerr champion the idea of having stories of 90-120 seconds in length at your fingertips that illustrate the benefits to the buyer, specifically, of what you’re selling, especially in those situations where the buyer is likely to want to hear more (which they see in terms of benefits, i.e., the difference the product makes, not features, i.e., what it can do). In our context, that means having very short case studies and trying to get a few into, say, an assessment meeting, or maybe one in a very involved call with a trust.

Anyone who’s tried to do this will know it’s not easy. In an assessment meeting, for example, all the attention as regards the service under discussion is on the Services manager normally and the fundraiser tends to chip in occasionally, rather than leading. That said, it’s good if one of you can be putting a human face on things. So, at minimum it’s worth bringing up in the pre-assessment meeting with the team who’ll be meeting the assessor.

3. Case studies

When we think of stories as Trust fundraisers, we normally think of case studies. You’ve got two big challenges, here:

a. Getting the case studies and information

Partly this is about working well with Services. This is a big section in another menu on this site.

However, even if Services are supportive, the chances are that they wouldn’t produce what you need. It’s possibly not their job to know all the detail. If not, someone would need to interview the service user. (If you don’t have a totally anonymous case study, you should get their permission for using them due to GDPR. So, you almost might as well interview them and get a better product, then.) Services won’t (from experience) really understand how to do that, so you’ll either need to step in or train them.

Key points about interviews:

- You need to get the service user very comfortable (even though some things might be a bit difficult to talk about). If they’re voluble, you’ll get a much better case study from picking key points from a heap of material. (Some of this is about Services selecting the right person in that sense, as well as having a good story to tell.) Thank the service user for their help (and actually try to be grateful – a problem with some trust fundraisers is they can be a bit by the numbers” and not feel it). Highlight that their story will help you get funds so that other people in the same circumstances can get the help they need. Be yourself, but – it’s good to be empathetic. I heard one professional interviewer for case studies saying she would sometimes shed tears with her interviewee. Ask them to tell their story, rather than talking in fundraising jargon.

- Let them talk so they get comfortable, but at some point you’ll need to supply structure, or you won’t get everything. The best approach is: (1) What intervention did they actually get? (2) How did they benefit from it in the sense of, how did their life change? (3) If it’s not obvious: how did the service create that change to their lives? (4) Given the change in their lives, what was the corresponding situation in their lives before they used the intervention?

- Get details about them as a person – a case study is a story and you want a bit of colour so people are interesting and the reader sees them as a human being. It’s also worth getting their reactions to the service and what happens to them.

- Once you think you’ve got everything you need, it’s worth asking “Is there anything else you want to say?” The interview may go on for a bit after that – they’re relaxed, they don’t think of it as part of the process, they probably feel very “heard” and may want to carry on. There can be very good stuff come out at this stage.

b. How to tell great stories from the material you get

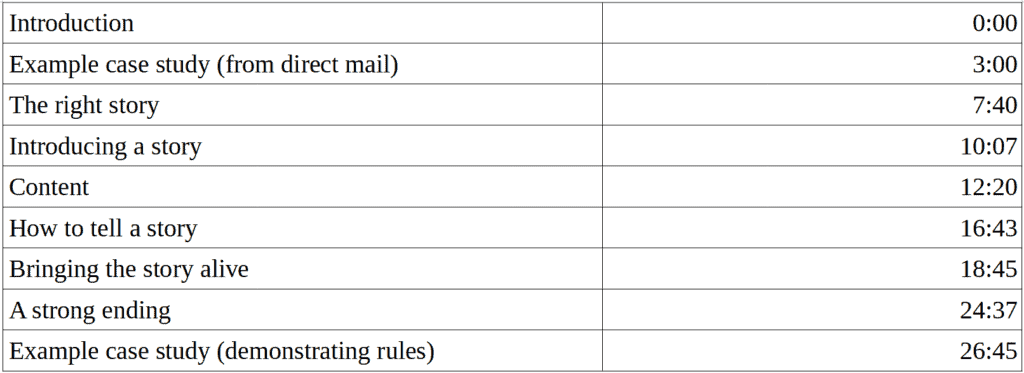

The following video is a training presentation on telling stories:

If you find are interested in this approach, there are more ideas, again, in the videos on using emotions in trust fundraising. These are under the general writing techniques sub-menu.