Photos: Mart Production and (insert) Christina Morillo, on Pexels

This area of the site was written for very experienced trust fundraisers.

Photos: Mart Production and (insert) Christina Morillo, on Pexels

This area of the site was written for very experienced trust fundraisers.

This section is for trusts team managers and people trying to move into management:

The following section covers considerations specific to our field.

In passing, though: there’s a strong case for prioritising learning good line management skills, even more for us than in other management roles. Trusts staff maybe experience more challenges than some roles and it is easier for them to leave.

As individuals, we tend to have good people skills to build on. However, quite a lot of us are by habit a bit “head down”, introverted, productivity orientated. A lot of us don’t have much experience of good managerial support, because our own managers didn’t understand what we did. So, it can be a bit of a challenge for us to really appreciate the trusts team managerial role or to give staff the support they need.

I’d suggest you make staff retention a key part of your strategy. Recruitment agencies will tell you that people typically stay in a trusts post for under two years. There’s a shortage of people, the staff who work for you are good at applying for things and yet our team targets often assume the posts are continuously filled.

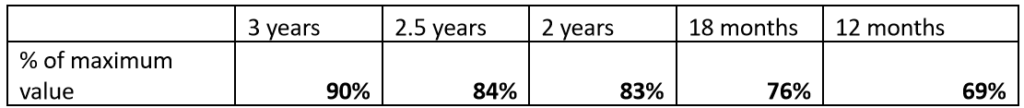

Let’s suppose it takes 3 months to fill a post, 4 months for them to get up to speed and they build at an even rate. This is roughly how much of the maximum amount you’d raise over the years, depending on the average length that someone is in post:

No doubt you could reduce the drop by focusing on the most important work. At the same time, it’s only in the easier roles that people will be properly up to speed in 4 months.

Frankly, there IS only so much you can do to get people to stay, but you can help:

In most charities, these issues are picked up mainly in six monthly or yearly appraisals. However, if someone will be in post for just 18 months, they may decide between appraisals to go. It could be wiser to also consider the matter at 1:1s.

It’s not always an emotionally easy job. There are opportunities to spot people’s emotional resilience in recruitment and it’s worth including in the person specification. However, you’ll be aware that it’s hard enough to get good candidates. So, why make the job harder than it need be?

I’d personally say you’d be a better manager if you care about everyone who reports to you. Otherwise, they may adapt to the stresses in ways you don’t want: leaving; losing motivation; being less productive; taking less responsibility; becoming process- rather than results-driven.

People won’t feel comfortable with high expectations if they feel unsafe. I’ve tried to predict and be proactive in raising the kind of stresses my reports face, highlighting that experiencing stresses can be natural but there are things that can help. This has often (though not always) created a sense that it’s worth them disclosing problems.

Likewise, people tend to open up when they think it’s safe and useful to do so (though they may not, even then). You have to work to create that sense.

A lot of issues (such as internal politics) are covered elsewhere in this site. However, the following are emotional issues you may well need to address specifically:

Trust fundraisers have to handle a lot of uncertainties and they have more responsibility than power. If you approach your report’s job honestly in that way, communicating with them and judging them accordingly, you can reduce a lot of that stress.

Some consequences, for me, are:

Be careful how you treat failure. To quote Amy Edmunson of Harvard University, ‘When I ask executives to consider this spectrum of reasons for failure and then to estimate how many of the failures in their organizations are truly blameworthy, their answers are usually in single digits—perhaps 2% to 5%. But when I ask how many are treated as blameworthy, they say (after a pause or a laugh) 70% to 90%.’ She has a great talk on how to ensure people learn from failure, based on being open that it’s happened.

Trust fundraisers need to feel they can fail and learn from failure. It’s part of the job, like any other. However, managers can respond to the pressure of targets by saying “This is all fine, it will all work” and it puts pressure on people to conceal mistakes and/or start looking to leave when the situation when they can’t handle their responsibilities. If they’re no good at their job and can’t or won’t improve, they’ve got to go. Your service users absolutely need you to make that decision. However, otherwise, it’s a phase they need to go through. You should welcome with them their introduction to the real world, while expecting them to learn to go beyond where they are.

It’s also a fairly isolated role. The person working for you probably spends a lot of time not talking to anyone. The people they’re working with are normally not the people around them. Their contacts in Services often have great people skills, but it’s not always an easy relationship, due to competing priorities and the fact you’re trying to get things from them. It’s easy to feel quite detached.

Things that I think have helped are:

Once you’re past the learning curve, the role can get tedious, especially for people in entry level roles (who are probably used to lots of learning, but whose jobs can be more repetitive). It’s more an issue in full time than part time roles. If they think there’s nothing in it for them to highlight the issue, your report may hide it from you – why admit a “weakness”?

Things that have helped are:

Hayley Gullen summarises some arguments against giving a ridiculous target and discusses in length that it would be unfeminist to do so. The blog post is 1 March 2018: https://scepticalfundraiser.com/page/2/

You can feel you’re at the bottom of the tree when you’re in early trust FR jobs. You have to work with managers and senior managers who seem to know just a tonne more than you do, who have better people skills, etc. I think there’s more of a place for bigging up your staff: noting the things they do well, spending time on appraisals, amplifying their messages, attributing their ideas to them with others, making sure people are aware of their successes.

This should have the usual benefits you’d expect in any job: if they feel trusted, they’re more likely to be open; if you’ve shown loyalty to them, the chances are they will reciprocate; a 2004 study published in Harvard Business Review found that for the highest performing teams, the average ratio of positive comments to negative ones was 5.6:1.

The case for a culture of development is:

A famous management quote, attributed to Henry Ford amongst others, is ‘“The only thing worse than training your employees and having them leave, is not training them, and having them stay”. My own experience is that development is something we agree with in principle but gets pushed out by:

(a) The demands of the job. Reports don’t think they have time.

(b) Not really thinking deeply about what it means. If the staff member’s development plan is tacked on the end of the annual performance appraisal process, when everyone’s tired and the plan is basically to continue business as usual, their development plan may be a bit ineffective.

Ideas to help are:

Feedback on proposals is important and helpful. However, it does create another time pressure and when you feel you’re struggling a bit, it’s easy for feedback to feel like another slight criticism. If this is an issue, things I think can help are:

If people can set their own targets and KPIs, it’s more motivating, they have more ownership – and once you’ve got past the “How can we know?” stage, they tend to set more stretching targets. However, it’s worth doing your own analysis, mainly so they don’t set themselves up to fail.

With KPIs, it’s easy to “game the system” in trust fundraising. So, even if you don’t look at everything going out, it’s possibly worth seeing a selection and feeding back on it. You have final responsibility for quality.

Briefly moving away from very trust-specific information: It’s also worth remembering that the major guru of Management by Objectives, Peter Drucker, didn’t define objectives purely in terms of income, or productivity. He thought you could set objectives in the areas like: market standing; innovation; and attitude.

I personally think there’s a bit too much emphasis on targets at the end of the year and not enough on the mid-year point. If you look at other disciplines – sales, for example – targets are often looked at quarterly. My own tendency, and some other trust fundraisers I’ve seen, drift a little during the summer, get very serious later in the year and at some point get a little freaked about the targets. That’s because they’re treated too much like an end of year exam, rather than more continuous assessment. You can’t realistically work towards quarterly targets, but you can a bit with six monthly ones. Hence, the suggested change in focus.

With a post working with smaller trusts, management by KPIs and quality, then supporting them to trouble shoot and develop where there are issues, will get you quite a long way, in that productivity, efficiency and quality are important components.

However, at the other end of the scale, with the biggest applications for the newest work in the most flexible organisations, the post-holder is really working in a “Three I” role (information, ideas and intelligence) in a “task culture” (to use terminology from management guru Charles Handy). In that context, management in terms of providing support and development but being flexible about objectives, is key. Also, how to support someone to do a more task-centred job in a department and organisation which might be more about very clear divisions of roles.

Although the year’s target is, in a sense, the rationale for the post, challenging but achievable shorter-term goals are much more motivating (Martin, Goldstein and Cialdini, The Big Small, 2015).

As stated in the “work with Services” section, people tend to under-estimate the likelihood that someone they approach for assistance will help (Flynn, F.J. & Lake, V.K.B. (2008). If you need help, just ask: underestimating compliance with direct requests for help. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 95(1), 128-143. The researchers believed that the reason is that people tend to focus on the cost of the task but under-estimate the “social costs” (embarrassment, awkwardness, etc) of saying “no”). Yes, you do need to be the one person in the charity who really “gets” the problems your reports have, but it’s worth probing a little and trying to build a bit more culture of support from Services and Finance.

In small teams, there’s potential for jealousy/resentment. For that reason:

One of the really weird things I’ve found about fundraising is that people never talk about the fact we’re trying to do good in the world. There’s often a pretty direct connection you can make between a trust fundraiser’s job and more people in need being better off. However, I’ve only once been praised in that way.

There’s a lot of management theory these days about being purpose driven (e.g., the work of Simon Sinek). Doing your job to make the world a better place is potentially motivating, makes the work fulfilling and can give you more clarity. However, in our sector we talk a LOT more about targets than about people.

At the same time, we live in a slightly guilt-driven society and people need to avoid burnout and be able make mistakes without worrying they’ve screwed up the lives of vulnerable people forever! Otherwise, they won’t grow and nor will they grow your charity. So, I think there’s a time to say, “Well done, homeless people are SO much better off for having you here” and a time to be saying: “If you don’t forget all that, you’ll go mad. It’s just a job.”

In most trusts roles, the people you manage will have to fend for themselves: using what works for them, feeling confident, resilient and self-reliant, problem solving, being independently driven. While they’re with you, they’ll also be easier to manage, leaving you the time to try and develop them.

Things I have found personally to help are:

You’ll need to balance this against the times when things need to be done as a team – e.g., what you share, or where services may reasonably expect a common approach from your team. However, you’ll usually get more from your reports and set them up better for the future if you let them be the best they personally can be.

Occasionally you’ll want to use freelancers / consultants to help with the work. The following are some considerations: