Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplas

This area of the site was written for very experienced trust fundraisers.

Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplas

This area of the site was written for very experienced trust fundraisers.

If you’re stressed with the job, you’re really not alone. (It can just seem like it.) Trust fundraising can vary between very interesting (with moments of elation) and sometimes really quite stressful. If it’s often stressful, there’s likely to be something wrong. However, to quote The Porcupine Principle, Jonathan Farnhill’s general book on fundraising: ‘If you are finding fundraising hard work, you are probably on the right lines because it was never meant to be easy nor was it claimed to be.’ No one is normally going to physically attack you or expect you to work 18 hour shifts like some jobs, but there are challenges.

However, if you’re in it for the long haul, you need to find ways to stay positive, motivated and resilient, to be positively, not negatively, challenged. Some people think they need fear or anger to function well. However, you can get burnt out, lose energy, enthusiasm, creativity, breadth of vision and judgement. If you can relax but stay motivated, you may find that in a lot of situations you will bring a lot more to the job.

I’ll go through some of the issues we face and then cover some general points about looking after yourself.

Whilst you can (quite reasonably) lose your job because you aren’t very good, you won’t lose it for just missing your numbers. In over 30 years at over 30 charities, I’ve never been let go for missing my target. I’ve had two roles that I couldn’t do very well, due to very high expectations of productivity, where I’ve probably jumped before I was pushed – but that’s about my personal suitability to the specifics of that job, it’s not about the numbers. I’ve not met anyone who was let go due to missing their target (though one person I mentored we needed to reassure the hierarchy that the post itself wasn’t misconceived and there was real potential in the post).

Missing targets/KPIs can be a symptom of a genuine problem for management to get concerned over. However, in a role where you have more responsibility than power, where there are lots of unknowns and probabilities rather than certainties, where targets often aren’t set that scientifically anyway, missing your target can also be just one of those things that happens.

A problem that follows is that you could do with knowing what your manager really thinks at this stage and things aren’t always clear (e.g., the conversation has got no further than “We need to make up the income”.)

If you have the ability, the charity would be fools to get rid of you. Trust fundraisers who’ve shown they can do the job are usually a scarce resource. (Not at the time of writing, due to COVID-related redundancies, but at every other time.) If you did lose your job, you’d very probably be able to find a way back into work – I’ve seen one or two fundraisers been forced out because they were terrible who’ve managed that. (For clarity: my personal opinion, for what it’s worth, is that if you are a poor trust fundraiser and cannot improve, you should think whether this is the best career for you. Anything else is unfair to the end users.)

In fundraising team reforecasting meetings, you see that some of the teams are, actually, missing their targets. It’s a natural part of the fundraising process for it to happen at times. You make a very educated guess at the numbers (or have them handed down from above) things work out differently in practice for a variety of reasons – including people not being perfect – and the Director of Fundraising is hoping that things will even themselves out across the teams.

When people set their own targets, there’s an instinct to set them higher and it’s easy to overdo it. It doesn’t make you a bad person if you don’t achieve your own unrealistic expectations – it just means you made a mistake, at a time when you were quite possibly too busy meeting last year’s target to do your target setting thoroughly. Perhaps you can chalk it down to experience.

Julia Ammon did an exercise on confidence and resilience at a Fundraising Everywhere trusts conference, where she got everyone to list three achievements that had nothing to do with money. She had a great point – we all talk about ourselves in terms of what we’ve raised, but it is only part of the process. I know that some of the things I’ve done the very best didn’t raise any money at all. They were still great and I try to be just as proud of them.

The very experienced fundraising director, Mark Astarita, told me he thought good trust fundraisers were target driven and that they could lose and regain that. I totally agree and encourage people to cultivate a strong desire to succeed, for example by really celebrating their successes. However, you also need to let go when things aren’t working and to see yourself as bigger than just the money you raised. Then you can go again, focussing on what you CAN achieve.

When I’ve mentored stressed people, the stress has often been because they aren’t getting what they need from Services (and they feel quite isolated with it). There are things that can help, they’re one reason for the pages on this web site about working with Services and it can be a mistake to give up, or try to hand off the situation to your manager who doesn’t understand. However, people often aren’t doing badly – it’s just a difficult situation.

Another issue of responsibility is that you can see a direct connection between what you’re raising and people getting help and keeping their jobs. If you cannot control the situation, though, it’s important not to beat yourself up about it – especially the small failings that we all experience.

It’s good to expect a little more from Services, rather than less, because: (a) you’re usually either going forwards or backwards; and (b) behavioural science teaches us it’s easy to under-estimate people’s wish not to refuse/disappoint others. However, the truth is that, especially in some places, trust fundraising can be a lower priority and some staff get very focused on just their top priorities.

Dealing with rejections is a matter of practice. As this site targets more experienced fundraisers, hopefully you mainly see rejections as just part of the job – if you didn’t get rejections, you’d be doing something very wrong because you’d only be going to the very best prospects. There are few niches where things are so predictable (and worth the time) that you can develop extremely high success rates.

If you’ve invested heavily in an application, it’s hardly surprising if you’re knocked back in some way by a rejection. It can help if you can accept that you’re just going through a process of dealing with that – and use it to learn what you can as you fume, or fret, or whatever, but otherwise to be patient with yourself and wait it out.

My own experience with the very big, important rejections can be that there’s a limited period afterwards when I can’t do that much, except maybe analyse and try and think how to improve things in future. Then there can be a longer period where my motivation isn’t the same, I maybe get more self doubts and ideas for improvement are probably still coming occasionally. Then my enthusiasm builds properly back up over time and I’m ready to go again in a bigger way. It’s really not nice to go through that, but I don’t worry because I know it’s just a process.

It’s a good situation to use Julia Ammon’s advice in her Fundraising Everywhere talk and to re-frame things, as her examples illustrate. Rather than settling with the thought “I failed because we didn’t get that grant” to see can you think “I did the best I could with the information and resources available to me”. Rather than thinking “This failed application means I’m really bad at trust fundraising” can you think “I learned so much from this failed application – I’ll make the next ones better!!”

There are a number of elements to this:

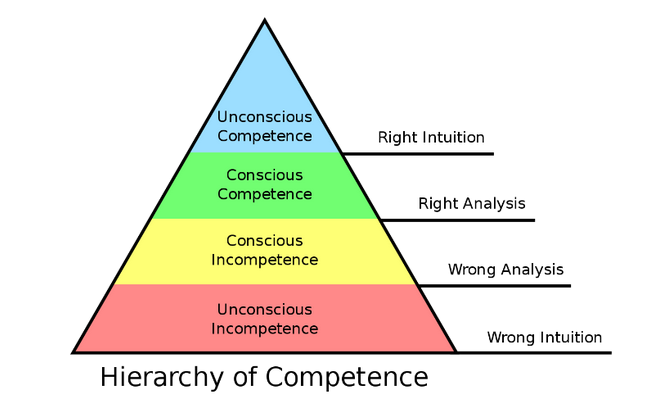

Source: Wikipedia

The Pareto Principle notwithstanding, in a lot of trusts role you’re expected to keep going, continually meeting deadlines. That can be how you really succeed, too. It’s much easier to keep going if the job’s more of a pleasure than a struggle. If you’re finding it relentless, maybe:

Some Trusts jobs just are exceptionally busy, though. If your management can’t find a solution for that and it doesn’t suit you, there may be alternative roles that you’d fit better.

My experience in the early years as a fundraiser was of a lot of guilt when I wasn’t delivering – either because of a lack of skills, things were very blocked or I’d got burnt out and now wasn’t trying hard enough. It’s possibly no bad thing to be moved by your failure to live up to reasonable standards that you set yourself. However, beyond that, if you’re having a decent go at the job, guilt doesn’t actually achieve the objectives it aims to. If you dislike the job because you feel bad about how you’re doing it, you’re not likely to apply yourself as effectively, at least over the long term.

My own experience in that situation was that trying more to just see it as a job, to let go of some of the sense of responsibility, allowed me to enjoy and so better apply myself – making more difference for people in need. We aren’t selling paperclips and it’s truthful to know that. However, it’s a balancing act – finding a “sweet spot” where you are behaving ethically and the work is fulfilling, whilst not burning out, feeling you need to move on or messing with your head.

There are lots of great things about growing up in a strongly Christian-influenced culture, but we do arguably experience more guilt than other cultures and in a job where you have real-world responsibilities like ours it’s easier to fall prey. A longstanding Buddhist teacher, who has had heart-to-hearts with many thousands students, once remarked that we judge ourselves so harshly that if we took the same attitude with others, not even Hitler or Stalin would employ us in their courts. Looking at things objectively, you might find you should “come off it” a little bit.

Being let down and messed around by your manager will happen every now and again in our field and it can be immensely frustrating, especially when they tell us to do genuinely stupid things.

We may be managed by someone who doesn’t fully understand or appreciate our work and they can be constrained by some of the internal politics, which blows through our area of work more than others.

It’s a lot more common with managers who aren’t trust fundraisers by background and who’re very interventionist. However, you also get people who once did a year of trust fundraising (where their work may not actually have embodied best practice) and they now think they know the One True Way.

It can be hard enough to struggle with outside forces, without being sabotaged by your own manager! Especially if you feel you have been going above and beyond the call of duty – I’ve seen people develop a huge amount of pique and resign at that point.

Action plan:

There can come a point in a Trusts job where things seem very same-y. (For me, it used to be after maybe 18 months.) It can become grinding for some people. Some ideas to help are:

There’s a correlation between negative thinking and stress. That’s not to say that it’s easy to change all your thoughts to positive equivalents. However, finding things you can reframe positively does work for quite a few people.

Rob Woods, fundraising guru, suggests to fundraisers (including ourselves):

At the time of writing this, I’ve just been through a pretty bad year. (I gave so much effort and focus in my spare time to this site, it affected my day job.) Thinking every other day about what I’d learnt, and alternating that with thinking about my successes, has helped me see my problems more as learning, which is useful both to me and to my charity. (It’s also helped me allow my mind to compartmentalise, so that when I’m working I’m really switched off from this web site!)

Everything above is more to do with a trusts job. However, it’s well worth thinking about general techniques for dealing with stress, as well. There are lots and lots and many (not all) can be combined with each other:

1. Worries can have a valuable place, in identifying possible concerns. (Anxiety is not very good at then evaluating the issue, or identifying or implementing solutions.) Rather than completely suppressing the worry, noting it and evaluating it in a positive, relaxed way when you are more settled can help you use your capacity to worry in a positive way – making friends with yourself.

2. If in practical terms, you’re doing great and you’ve got “nothing to worry about”, maybe the answer is just to think/talk that through in some way.

3. Adjusting your work in some way could help with stress. Just one example: you might decide you’ve been on too much of a learning curve for too long, or you need a break or a gentler learning curve.

4. Practical anxiety coping mechanisms. There are lots of simple things you can do to reduce anxiety. Here’s a list from the NHS, but there are lots of tip-type lists out there: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/stress-anxiety-depression/overcoming-fears/.

5. Wellbeing and Recovery Action Plan / Wellness Action Plans: This is about planning what strategies you can adopt practically in a particular scenario – for example, at work – to head off and reduce stress: https://www.mind.org.uk/media/1593680/guide-to-waps.pdf. WRAPs/WAPs are really a framework to be proactive in thinking things through.

6. Physiological stuff that promotes relaxation and wellbeing:

Studies show that for some people, exercise, for example, is as effective as medication in reducing anxiety. If the body’s less stressed and producing more endorphins for physiological reasons, you feel better.

7. Binaural Beats: You maybe don’t want to use binaural beats indefinitely, but they do work well to calm you down in the short term. The gist is that, by listening in different ears to sounds that are slightly out of phase with each other, it entrains your brainwaves to adopt corresponding wave patterns for alpha, beta or delta waves. That may sound a bit like new age mumbo jumbo, but it does actually work: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wa9YSAdbKh8. There are lots of “binaural beats for focus at work” videos and podcasts, others to help you get to sleep, and so on. You’ll need to be wearing headphones for this to work.

8. Meditation. There are three kinds of basic, calming practice:

…if you want to extend the period of the exercise, then once you recognise the accepting mindset, you can combine that with a little bit of attention to your breath, just to give you a way of staying in the present moment which makes it easier to be accepting. The breath is always happening in the present.

There’s a lot of clinical evidence for the effectiveness of mindfulness, less so for other approaches, though insofar as they overlap with the next item there have been trials. There’s also a lot of evidence from their use over millennia by different, mainly eastern, religious traditions: they’ve survived down the ages because they work.

9. Positive psychology: This is other stuff to cultivate a positive mindset (things like exercises to cultivate gratitude). Randomised Controlled trails indicate it can be as effective as cognitive behavioural therapy, at least for depression: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Positive-Psychotherapy-Clinician-Tayyab-Rashid/dp/0195325389

10. For some people, adopting much, much more positive and confident body language, maybe with a much more positive focus and language, can make a quick difference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ezSkpyuhymk. I don’t know if there are any relevant clinical trials.

11. General tips for better work:

12. Psychotherapeutic interventions (things like counselling). Many workplaces offer telephone-based counselling. The main thing that stops us using them is usually stigma – not wanting to admit to having a stress. However, a lot of people who’re brave enough to push past that do find they learn useful skills/techniques or just have very positive and usual conversations.

13. It might be worth looking at the resources around HALT – being Hungry, Angry/anxious, Lonely and/or Tired. Some look a bit at work consequences and unexpected things you can do – for example, if you’re hungry, you’d apparently be better off eating nutritious food, also if you’re angry a lot (not a problem I get) exercise apparently really helps.

All of the above consists of ideas about dealing with “lower level” stresses, rather than out-and-out depression, anxiety or other conditions. If you think you might have mental health issues at that level, you should see your GP, or a fully qualified counsellor.

A close friend with very chronic mental health issues got quite a bit out of going to one of the local Mind-type community services, because there’s a lot you can also learn from peer support from people who’re clued up and in recovery.

I care for someone with quite severe mental health issues and always think I should use those services a lot more, myself.

My own experience of bad mental health in my teens and twenties – and that of a number of friends – is that the worst bit is just admitting that there is something wrong. After that, there is help available – and the earlier you can go, the more problems you prevent.

Further reading