Photos: Ameen Fahmy and (insert) Forty Two, on Unsplash.com

This area of the site was written for very experienced trust fundraisers.

Photos: Ameen Fahmy and (insert) Forty Two, on Unsplash.com

This area of the site was written for very experienced trust fundraisers.

If you look at true start-ups – people working in fields with extensive uncertainty – then their experience is completely unlike that described in our proposals:

…and so on. (I saw this myself when I tried consulting: ringing my potential customers – Heads of Fundraising – it immediately became clear that the things they’d actually buy from me were very different from the things I’d hoped they would pay for.)

Steve Blank, Serial entrepreneur and Stanford Professor of Business, likes to say “There are no facts in your building. You have to get out of the building to find them.” When confronted by the real world, the ways you think you can make a difference can turn out to be very different.

This isn’t really just about commercial businesses. It’s highly analogous to our own worlds. People pay businesses for products because they have needs and that creates the demand for the service. If we think that demand isn’t as important for us, or that the end users shouldn’t have the same kind of control over needs because they’re not paying, then that’s deeply patronising and patriarchal.

However, if the entrepreneurs above had been funded under a proposal for a grant, they’d have failed! Almost guaranteed! For two reasons:

However, those companies pivoted to do something else because it turned out to be a much better idea than the one that was originally proposed.

Think about where the projects in our proposals came from. Some person had what they thought was a good idea. Either they were passionate about it or there was money from a funder and the idea took wings because FR was pushing it. However, the person having the idea was extremely busy doing their day job and barely had time to work it up into a coherent model, never mind reality checking it.

If that’s how different the real world probably is to the whiz bang new ideas you’re trying to fund, and if you want to be part of the solution, not part of the problem, how does it change your work?

You need to engage your funder well enough to clarify if they’ll go for genuinely pioneering work. If you then aren’t prepared to engage with Services and go back to the funder when there are changes, you’re doing your service users a disservice, by trying to force the organisation to deliver an inferior service.

It’s hard to come up with an idea that fully fits your end users. The vast majority of businesses fail because they don’t understand their stormers and I think there’s a lot of similarity with charitable services: we don’t not understand either the end user or the partners that we need to work with in order to access them. That looks like either far too few service users using the service or the anticipated benefits not coming through.

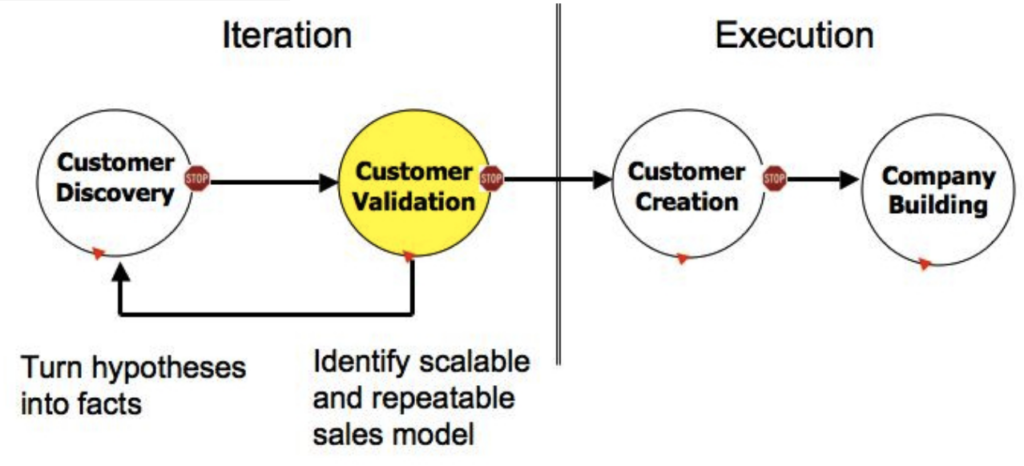

However, there’s a cycle developed by Steve Blank for start-up businesses, that will enable you to get closer to the right idea:

Blank has a subtle and sophisticated process that’s spelled out in his book The Four Steps to Epiphany.

The key, really, is that even before you need to have made contact with end users (and any other key parts to the delivery, like the youth clubs through which you’re going to deliver the service) and really discovered from them precisely what their issues are and what they need and who’s involved in the decisions as to whether to go ahead and why. You’ll know when they’re on board with your ideas, because they’ll stop politely answering your questions (because they’re nice) and start making demands of you. It’s only when you’ve got real clarity from them about what they need from you that you start putting the full idea together – and even then, you only know it’s right when the end users will really commit – meaning plenty of time, given that they aren’t committing money.

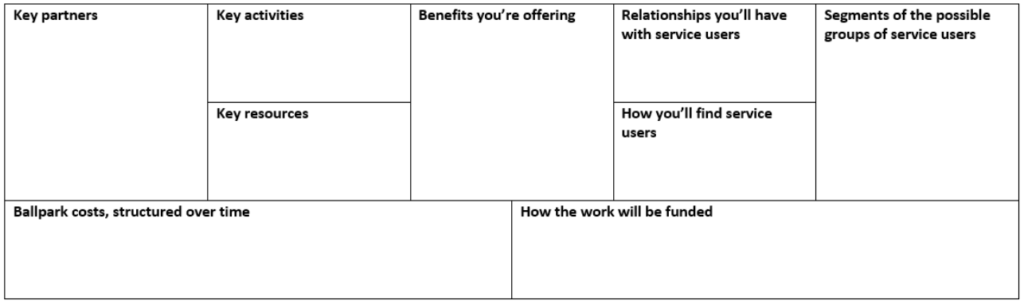

One tool that’s worth considering is a modified version of Alex Osterwalder’s Business Model Canvas:

Osterwalder recommends that, when brainstorming the business that’s your solution to the issue, you don’t just do one of these, but you spend five or ten minutes on each of several possible solutions, then choose the best one.

Osterwalder and Blank would both make the point that, in the real world when things are uncertain, you should be using a big sheet of paper and using post-it notes to put points on – because ideas will be swapped in and swapped out as you go along and test things against actual realities. Whether your organisation can tolerate that level of flexibility will be interesting to see!

Once you have your project, if it’s original enough, the chances are that it still won’t work as designed. That means you need management processes that will enable it to pivot quickly into being something else.

Get really close to the customers as you put your ideas together (end users / NHS)

Everything that follows is from the book Lean Start-Up, by Eric Ries.

Recognise and rank the key unknowns

Making fundamental changes

Scaling up