‘Grantmakers reported that they have particular trouble interpreting the budgets that they receive from nonprofits… As one [foundation] commented, “[I}t has been so challenging to figure out how some things were calculated”’ Drowning in Paperwork, American report on trusts, 2008

Trusts don’t necessarily know much about your area of work, but one thing they’re often good at is budgets. There are a lot of professionals on Boards of Trustees and the ability to read a budget is a pretty common requirement in their worlds.

Do the rough budget before anything else

Your job is to approach funder for a certain amount of money for something. If you don’t know how much things cost, you cannot decide what to include or leave out of the project. That means you can’t accurately write most of the application – the project section nor, by extension, the outcomes nor, by extension, the need. Nor the description of an organisation that is highly suited to that project, expertise delivering whatever it is and so on.

Pare the budget down or put everything in?

As far as I’ve ever noticed, trust fundraising isn’t like statutory tenders: the funder isn’t looking for the very cheapest possible way of delivering and a significant part of the consideration is on value for money in that sense. Also, you’ll occasionally see trusts comment that they expect the budget to include the costs needed to deliver the project and if it doesn’t, how do they know it will work?

At the same time, I’ve occasionally seen trusts comment that something seemed very expensive for what it is. Also, if you’re a grant maker making grants to projects, you’re trying to achieve as much impact with your money as you can and doing it in the context where there are loosely comparable projects. So, if your project looks pretty over budgeted (or under-budgeted) that does raise questions.

Checking the budget actually adds up

Trusts seem easily to spot budgets that don’t add up, or where the presentation you give in one place is inconsistent with the presentation somewhere else. If there are last minute changes to the project, it’s particularly an issue. For bigger applications, I actually set up my spreadsheets where everything is interlinked, specifically to ensure the figures stay consistent.

Required level of detail

There’s a big difference in the requirements of “gift givers” – trusts making quick, intuitive decisions and spreading their money around – and “grant makers” who are looking much more closely at things with a view to making a much bigger grant:

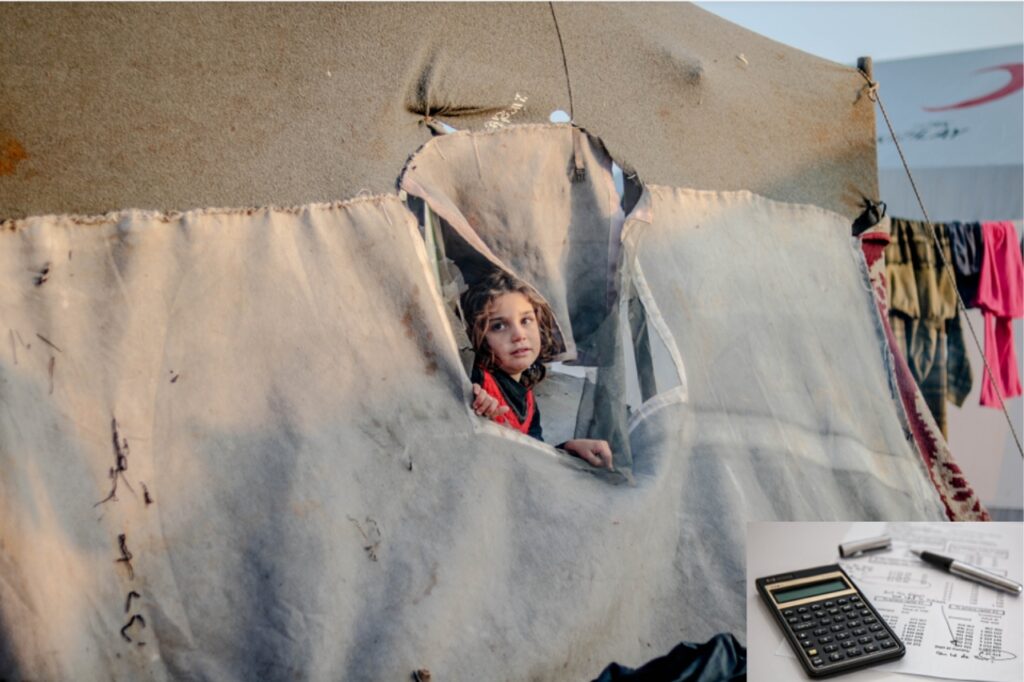

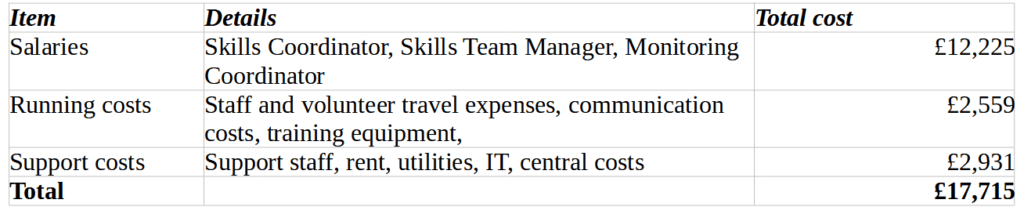

Gift givers

For most trusts likely to give up to £10k, one charity I was at used to just give summaries for the three main costs. The success rates were pretty good and requests for more details were very rare: