Internal records

The first key source is internal records. You’re the latest post-holder in a relationship, so you need to understand the relationship (even if it’s just one of continual rejections!) What you did with the Trust three years ago may be the last post-holder but one of you, but for the Trust it may only be six or 12 Trustees’ meetings back.

Maybe as many as half of all the problems I’ve ever had with relationships with funders have come from poor record keeping, bad handover and/or forgetting the detail of the relationship myself. You need to be up to speed.

Database

Charities generally have a database and if they aren’t at that level, there will be usually some kind of spreadsheet or at worst a Word document recording the same details. This should store details of all the contacts with the trust.

Folders

You need to skim the previous year’s papers, at least. Sometimes you’ll want to go back further.

Emails

I’d prefer to have access to my predecessor’s emails, as they may not have transferred everythign on email to the folders and database.

Hard copies

Although nearly everything is now kept virtually, once in a blue moon I’ve wanted to go back to the hard copies.

Financial records

Whether it’s from the database or somewhere else (e.g., the Finance people) I’d personally want the following financial information:

-

Details of the giving of any particular trust I’m looking at

-

Details of all gifts over the last year (dates, amounts and what the gifts were for) so that I can maintain relationships and my income budget / income flow for the year is grounded in something

-

The same details for each of the last five or ten years. This isn’t crucial in the way that the above records are, but its very helpful when you’re planning and evaluating:

-

Has the charity succeeded in fundraising for X in the past? Only the once, or pretty much continually? How much has income varied?

-

How much does income from trusts vary from year to year?

-

Can I spot key grants that are coming to an end?

The trust’s website (if any)

If you’ve time, skim the whole site, if there is one. Trusts often aren’t skilled communicators and may put the key piece of information somewhere you don’t expect.

When I see experienced trust fundraisers mess up their research, its generally either because they struggle

The Charity Commission’s register (and its equivalents in other countries)

Every charity has to send its accounts to the Charity Commission and they appear on the Central Register, as well as some other brief information about the charity. This includes charitable trusts. It’s worth skimming each section of the trust’s entry on the Register, until you get used to what the Register contains.

The register includes details of trusts based in England and Wales. There are similar registers in other countries. For example:

-

Search for “OSCR” to find the register for Scotland

-

In Northern Ireland, it’s the Charity Commission for Northern Ireland

-

If you’re trying to use this site in the USA (it’s really designed for a British audience) the best free starting point might be Guidestar

The main thing in the Register is the accounts.

How to research the trust from its accounts

By the time you read the accounts, they’ll be very out of date. However, it’s often the best information you have and trusts tend to change what they do very slowly. So, you have to rely on the idea that if they were following X policy back then, they are very likely still doing it now. And you’d normally be right.

There are normally three parts to the accounts that are of interest:

1. The narrative at the front of the accounts

Some trusts just send their accounts in because they’re supposed to and don’t make any effort to communicate what they’re really doing. However, others give a more or less detailed account of what they’re doing in the narrative section at the front. (I suspect they’ve realized that applicant charities read the accounts and they’re using them to communicate.)

2. Indications of staffing, under “expenditure” section

If there don’t seem to be any staff – or there’s maybe half a person and lots and lots of grants – then that’s useful to know. Unless the trustees are doing an exceptional amount of work, they may not have time to read very much, or even to consider a proposal from an applicant that they haven’t funded before.

3. Grants lists

Grants lists involve detective work. If you can spare the time, there’s a lot more that you can extract from a grants list than might initially appear the case.

If your job involves pumping out lots of applications for up to say £5k or £10k, there might be a case for keeping your research of grants lists simple. You might just “rinse and repeat” the project you sent the funder last time, or if they are cold, mainly settle on sending out one or two projects that are attractive, then use grants lists to finding trusts that give to your field of work and that seem more open to giving to new charities.

However, you can dig a lot deeper. I will outline techniques to learn a lot more – but do be careful with your time. It’s easy to waste time over-researching trusts, just as it’s easy to do too little for important opportunities.

a. Recognising funders of your overall area of work

You need to be able to recognize the names of charities doing the same kind of work as your charity (youth work, cancer research, fine art, etc). It’s worth looking on Charities Digest, any directory of charities at your local library, Googling charities in grants lists if you’re not sure.

You’ll need to work out what kinds of names are more or less relevant. There will be a pattern, but you can’t always guess it in advance. So, it’s worth looking at your existing donors. I was at a spinal injuries charity and we had a lot more joy with trusts giving specifically to physical disability than trusts giving to disability generally. When I was at a children’s hospice, it seemed to be irrelevant whether the trust had given to hospices for adults. At the Royal Hospital for Neuro-disability, funders of the capital works were often be funders of hospitals, but funders of the charitable running costs were funders of disability services.

b. Sizes of grant

How to guess at this:

-

Focus only on grants for your type of work. Just as you personally probably give more generously to some types of work than others that you support, so do trusts. They can give heavily to one thing and have just a passing interest in another.

-

Ignore the very biggest grants, especially if they look like an outlier. There may be nothing wrong with asking for the biggest grant, but when you think what the opportunity is worth to you, it’s worth bearing in mind that there may be something very special about that grant, such as a strong personal contact. Personally, I think in terms of a median (middle size) grant.

-

It’s worth quickly checking for other evidence as to the size: is there any indication the grants vary by size of project, or by size of the recipient charity, for example?

c. Chance of a grant (for a cold trust, based on the grants list)

Suppose the trust hasn’t been tried – or maybe only the once and you’ve got something very different to ask them to fund. Things to consider when guessing the chance of a grant are:

-

How far the trust varies its giving from year to year. If you compare the lists of grants in one year and the next and find they’ve given the same set of charities both years, then your chances are zero or close to zero. If the lists are totally different, your chances aren’t bad – a complete guess might be in the order of 25% or better?? If the lists have 50% of trusts being refunded, then somewhere in between.

-

What the trust says about the number of applications it gets. Sometimes this is in the narrative section of the Annual Report, or in a report from an earlier year. You can take account of the number of applications refunded and do a bit of maths to estimate your chances.

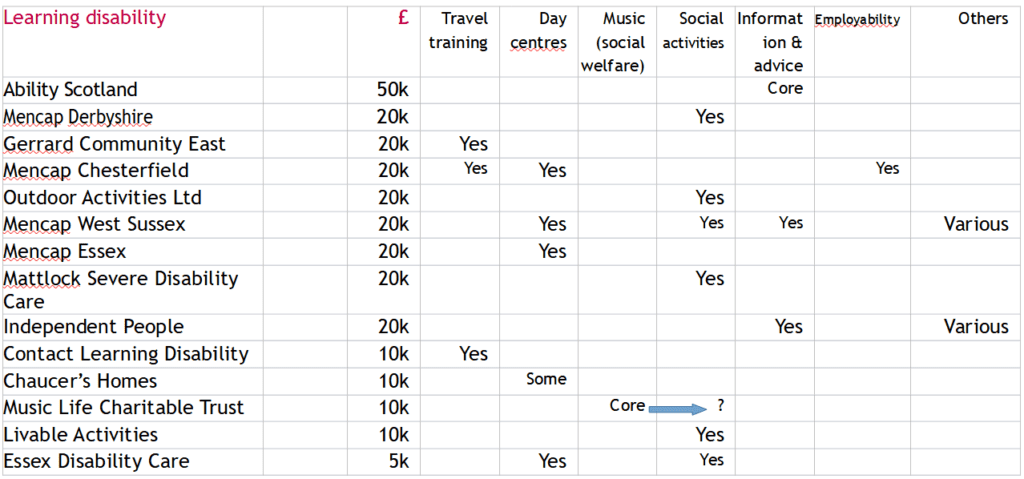

d. Looking more closely at what the trust is doing

This can be a bit more work. So, you’ll have to decide whether it’s worth it, given the size of the opportunity.

i. Geographic area

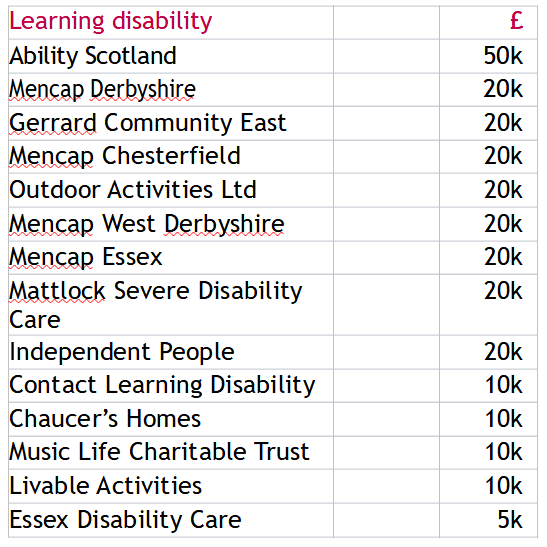

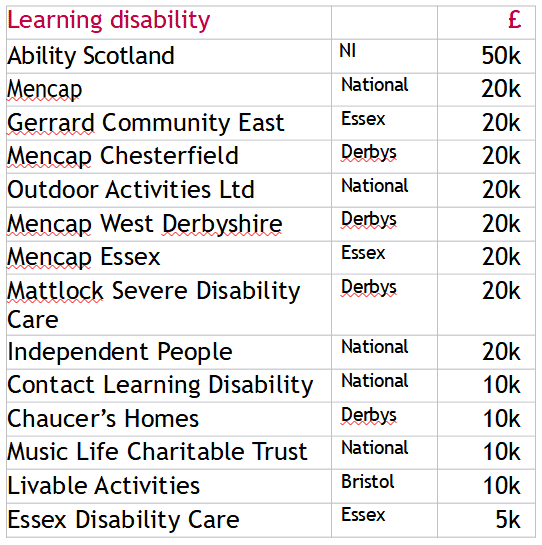

You need to be able to look at your trusts and identify where the trust is giving: