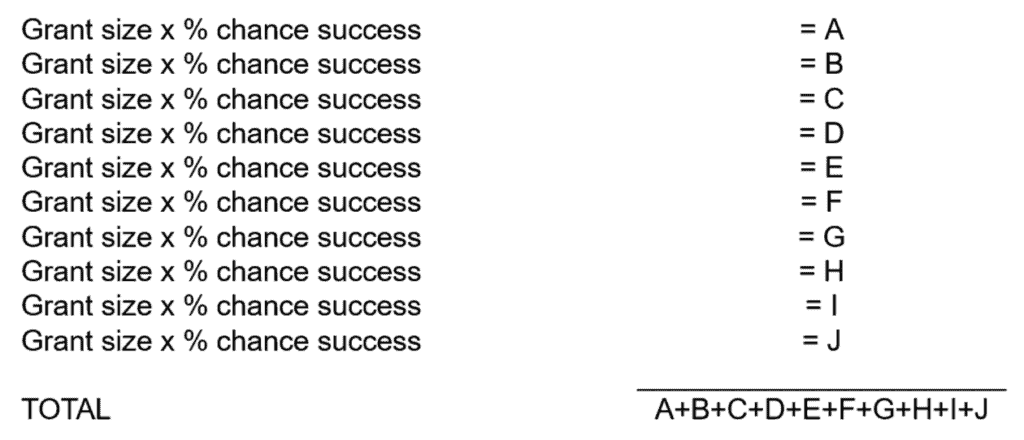

If you’re lucky, you can break that down a bit by individual services. However, the smaller the number of individual opportunities you have, the less accurate the process becomes.

I’ve used this technique since my Head of Fundraising at Age Concern showed it to me in 2002. It’s quite often been close, but it’s never been accurate. There are two reasons:

-

You’re dealing with lots of random things. The above process is a statistical technique to smooth out a bit of the randomness, but it can only go so far.

-

Trust income jumps up and down a fair amount because the biggest grants make up such a large proportion of the total and you usually either get them or you don’t. I once traced over five years the trust fundraising income of about a dozen national charities with total turnover between £1m and £2m. In nearly all cases, the income swung around, varying by a quarter or more of the Year 1 total in many cases and even doubling/halving in others. I’d be very skeptical as to whether the charities had all gone from excellent to incompetent and back again!

The obvious questions at this point are:

Years ago, Bill Bruty (a very good trust fundraiser and trusts trainer, whose course on target setting I strongly recommend) suggested to the Trusts Special Interest Group that people could use the following estimates:

-

20% chance of a lapsed trust giving again

-

40% chance of a trust that gave last year will give this year

-

60% chance that a trust that gave last year and the year before will give this year

-

80% chance that a trust that has given each of the last three years will give again

I’ve used those figures and found them a bit conservative for my own work (which emphasises strong work to maintain donor relations) but I expect it varies in practice with things like the way you work and how far your Services teams are delivering on their promises. When I went on Bill’s (excellent) target setting course and he’d changed from giving suggested figures to another method (which you should attend his course to learn). However, some people might find the figures useful as a starting point.

What about cold trusts, that have never given to you? It depends on how carefully targeted your applications are. I’ve seen it vary anywhere between 5% and 20%. If you’re struggling, I’ve seen other charities take a guess at income from cold trusts by looking at cold income in each of a number of previous years.

With warm trusts, you can use the previous year’s grant – unless that was exceptional for them, in which case there’s an element of “reversion towards the mean” that can happen.

With cold trusts, look at the range of grant sizes that the trust has given specifically to your are of work and see if you can spot any patterns. If you can’t, I usually use a middle size grant to do my estimates.

Developing contacts at trusts

A minority of charities raise a lot more money because they know someone at the trust. This normally works best in just two scenarios, though:

-

There’s an active “major donor” programme that you can piggyback on

-

There are things that are genuinely fascinating that you can entice a trust to come and see for themselves: research labs to wander around; projects in the developing world to visit; policy conferences of obvious applicability to the trust’s interests. It needs to be a lot more exciting than sitting in an office chatting to a member of staff.

If either of these situations is yours, I strongly recommend you read the book Grants Fundraising by Neela Jane Stansfield. I’ve seen people significantly raise their income due to this kind of contacts work.

However, most charities don’t have that level of opportunity. It’s still worth doing a list of key funders and circulating it to the people at your charity who might know someone:

Sometimes you’ll get lucky and it can be very helpful.

How many trusts to work with

If you’re at a charity with an established portfolio, the answer is probably: the ones giving to you and then enough to try and make up for the income you’ll lose from natural attrition.

A view that some of the leading trust fundraising trainers (such as Bill Bruty and Caroline Danks) have publicly signed up to is that you should have a portfolio of 50 trusts in total, because there’s so much work to be done cultivating them, and that many trust fundraisers are working with too many. I understand their view, but it’s clearly a matter of debate (as shown by the fact that most people are doing something else!) these figures assume you’re a sole trust fundraiser: if you are new to the sector and just focussed on the small ones, you might do well over 50, because they are quicker to work with indvidually.

In addition, some charities will have some kind of annual mailing, or mailing divided into quarters, to enable them to efficiently approach trusts whose gifts would be too small to be doing in dividual approaches. Not everyone in the sector agrees that it’s a good idea, though.

If you are starting from scratch, instead of continuing an existing trusts programme, you’d want to work with significantly more trusts. That’s because someone working with 50 trusts in the above example could be spending half of their time just servicing existing grants.

KPIs

There are weaknesses with just relying on end of year targets to see how it’s all going:

-

Motivation: Like other trust fundraisers I’ve seen, I personally am not so engaged with my income target twelve months before the end of the year (whereas four months before the end of the year it may be looming large but it’s too late to have big impacts). On the other hand, people seem to find monthly productivity measures are more immediately motivating

-

Getting you to address issues: if you know you’ve missed your KPIs for three months, you have a strong sense you should do something about it. If you don’t have to look, you may not even notice for a while longer.

-

Other measures of whether things are going well: there’s a slice of luck around meeting targets. So, other indicators of underlying health are useful for everyone on the occasions when the money isn’t coming in.

-

Trust fundraising in a thing of systems and processes. So, it helps to be monitoring how these are going. KPIs should reflect the underlying assumptions/logic of what you’re doing and if they’re off it raises questions. For example, at a charity where I was it appeared that the pandemic had put a lot more pressure on our ability to get warm trusts to give again (for different reasons we could speculate about). It’s only because we were looking that we noticed and could act on this important underlying trend.

You need to be a little careful to see KPIs only in their proper place, though:

-

The danger with them is that your job is reduced to fulfilling them – either by you or by your manager, who has no better way to manage them. You can “game” your KPIs, working to make it look like you’re meeting them, but finally it’s supposed to be about funding work, not meeting intermediate goals.

-

I’ve also had people work for me and get upset about not meeting KPIs, but then when we looked more deeply into the work, we agreed that they were actually doing it well. KPIs are a useful indicator, not a goal in themselves.

Good basic KPIs are:

-

Money raised

-

Numbers of applications sent

-

Total monthly amount applied for

-

Success rates with warm, lapsed and cold trusts and overall

Find someone experienced to look at your work/deal with your questions

One of the hardest things in trust fundraising isn’t understanding the basic principles. It’s making the judgement calls about what to do in the situations you face. When both Option A and Option B look reasonable, how do you decide? With long lead times before the results bear fruit and a lot of unknowns and a lot of luck, the calls are hard to make.

For that reason, it’s big help to find someone significantly more experienced to discuss your problems with. You’ll probably feel a lot more confident, learn a lot faster and do better in your first year.