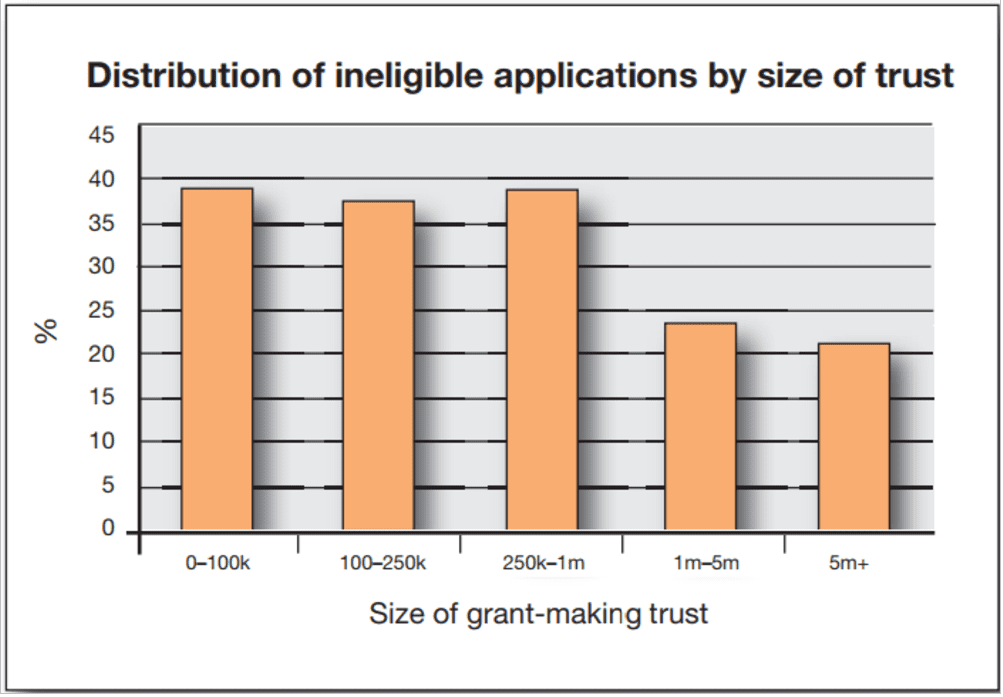

Two points about the second picture:

-

I’d assume that “ineligible” includes at least some applications that are technically “eligible”, but outside policy

-

Many applications to big trusts involve a lot of work. If you’ve done a lot of work, you don;t want the proposal to be rejected out of hand as ineligible.

There are a few different aspects to this key question:

a. Are you eligible?

All trusts use selection criteria. Quite often (not always) these are stated. Even if you have the world’s most genuinely amazing project idea, even if you are best friends with the chair of trustees, you may struggle to get funding if you are outside the criteria.

Don’t bother trying to find an extreme way to interpret the criteria, so you sneak in under the edge (or at least, if you do, then write the application extremely quickly and discount it!) It seems common for trusts to use their criteria to rule out work quickly and without much thought. There may even be someone whose job is simply to weed out ineligible and incomplete applications, so that the trustees never even see them.

b. Are you within the stated and unstated policies for who they give to?

Every trust operates according to policies, even if they aren’t written down. (For example, I worked in the grants office at a trust funding building projects, and because we were funding projects to last, we had an unwritten policy that we never funded charities that had been around for less than 10 years.)

Some of these policies you can see from the trust has written down. In other cases, you’ll have to make and educated guess at what’s going on, based on the evidence of what the trust has been funding.

If you are outside the trust’s policies, it will be very difficult to get them to fund you. (It can be very hit and miss even if you have strong, senior friends at the trust.)

Look out for what the trust’s policy is for each of the following:

Funding charities they haven’t found for themselves

Some trusts won’t fund “unsolicited” applications – i.e., applications they haven’t asked for. If they’ve funded you before, though (at least, in recent years) you can generally assume they’d consider another application: at a guess, the insistence on no “unsolicited” applications is just a way to stop the floodgates opening.

Funding charities they haven’t funded before

Closely related to the above – you’ll find that some trusts basically have clients and give little or not money to new charities.

Size of charity

You could be too big or too small for them.

Geographic area

Some trusts only fund work that will take place in certain geographic areas (e.g., the City of Ediburgh; or London Boroughs bordering the City of London).

Some trusts only fund charities that are based in particular geographic areas (so, you might be working in Slough, but because you aren’t based there, the trust isn’t interested). Occasionally, you see trust funding charities that are headquartered near a location, but that work nationally.

Characteristics of the end users (beneficiaries)

The trust might focus on people of a particular age (e.g., children) faith/ethnicity (e.g., Jewish) or disability.

Issues that the end users have

This could be anything from poverty to social isolation to an addiction. In the case of medical research, the aim may be to improve lives of / cure people with a disease.

Kinds of services

Although most trusts are focused on the needs and benefits to the charity’s end users, the trust might focus on particular kinds of interventions, e.g.: information and advice; medical research; interventions that involve volunteers; acquiring a high quality work of art; or recreational activities.

Elements of the actual work

Trusts usually give to one, or a particular range, of the following kinds of costs:

-

Short term funding, to get something off the ground (e.g., a new service, or an expansion of a service into a new area)

-

Funding towards the ongoing costs of a specific service (salaries, project expenses, probably a contribution towards overheads)

-

Funding a discrete project (e.g., a volunteer recruitment campaign to grow a specific volunteer-led service)

-

Funding for the overall costs of the charity as a whole

-

Costs of building: e.g., construction, purchase, refurbishment

-

Costs of equipment/equipment: such as a new scanner for a hospital; a minibus; a lot of bits of small equipment, applied for together. If a trust specifically rules out funding salary costs, bundling up the equipment costs for the project can sometimes provide you an alternative request

2. Valuing the opportunity that the trust presents for you

There are two things to take into account: the chance of getting a grant; and the size of any grant you’d get. As you normally do this by looking at grants lists, I’ll explain how under that section.

The chance of a grant

The following are some rules of thumb for trusts that have funded you before:

-

If they’re lapsed (i.e., they funded you within maybe the last five years, but aren’t funding you now) then a carefully chosen application reasonably well presented has at least a 20% chance of success.

-

If they gave to you for the first time last year, the chance of them giving again at the first time of asking might be in the order of 40%. (i.e., you cannot rely on it!)

-

If last time they gave to you for the second time in succession, the chance of the next application being successful might be about 60%.

-

If they’ve given three times in succession, you might guess at 80%.

Suppose the trust hasn’t given before: that’s not a good sign, if your predecessors have had a couple of goes and got nowhere. The chances are, they did as good a job as you will. Some trust fundraisers start writing trusts off if they’ve been given a few proposals and rejected them all. You need to look into the situation and see if there’s something that your predecessors have missed.

A mistake that beginners sometimes make is to look really pretty widely when trying to find people to fund them. In reality, maybe 85% or more of the money you bring in will come from a group of people that you’ll probably look at over and over as the years pass. They are:

-

Existing/lapsed donors

-

Trusts where your work is a very clear and unmistakeable fit with their policies. What this looks like will vary from charity to charity – for example, at a spinal cord injuries charity, we were substantially more likely to get a grant from a trust that focussed on physical disability than one that focussed on disability generally. (We did still get some grants from disability funders, it was just that there was a big drop in the likelihood.) On the other hand, at a children’s hospice it seemed like we were able to look at, in comparison, a broader group of trusts, because the cause was so very emotionally compelling.

3. What parts of your service to include in the application

Research is a crucial aspect, though nto the only aspect, to this. Considerations might include:

-

What the trust actually says. (Occasionally it will cover this.)

-

How big a grant and what proportion of the project is likely to get funded

-

Is there a bit of the total which you can pull out that looks much more attractive to the trust if it’s presented on its own? For example, if a national charity has a project that covers a big geographic area, they may go to a trust that just funds work in the one city for the proportion of that regional project that’s offered in the city. (They’re especially likely to do that if there’s something clearly happening “on the ground” in the city).

-

What do you think will look credible to the trust. Clearly, the better you understand the trust, the better you’ll be able to decide that.

-

Whether the staff internally will be okay if you cut things up. Suppose it results in you only getting a part time post where the work is currently full time. The charity may well think that’s better than nothing. However, occasionally they’ll be very resistant to you making such a cut down application, especially if they know this is the only application you can make.

4. What contents to include in the application and maybe how best to express them

As regards content: sometimes the trust will tell you this.

As regards the presentation. Suppose you’re fundraising for an activities project. If you can see that the trust funds projects involving volunteers, or addressing isolation, you’ll want to bring those aspects out much more than, say, any health benefits which don’t seem to be of any interest to the trust. (As long as you’re honest about the work, you can stress what you like.)

5. Getting the timings right

Trusts are generally very rigid when it comes to timings. So, if your application will be a waste of time because it won’t be considered for six months – or if the delay will make it look a lot weaker than if you submitted it in five months and the trust will let you do that – then you need to know the timings.

You need to ask when an application would be considered if you submit it by date X, not “When is the next meeting?” You might not get into the next meeting and occasionally trust administrators don’t say.

6. When is it worth researching the trustees?

If you’ve tried this, you’ll be aware it takes a lot of time. I’ve personally almost never found anything useful about the trustees’ charitable interests when doing this. I can think of a couple of good uses for researching the trust:

a. If you’re able to network to or meet a trustee

If this is the case, the more you know about them, the better. It might help you reach them and it may well help you have better conversations with them.

b. Medical research proposals

There are two distinct groups of trusts who fund medical research proposals: medics and laypeople. If the proposal is going to a medic, you need to work harder at ensuring scientific accuracy and the precise terminology. If it’s going to a layperson, you need to work harder at ensuring it is completely comprehensible to an ordinary person.