Photos: Marcus Aurelius and Pixabay, on Pexels

This webpage is for trust fundraisers with three or more years’ experience. Beginners should use this page instead.

Photos: Marcus Aurelius and Pixabay, on Pexels

This webpage is for trust fundraisers with three or more years’ experience. Beginners should use this page instead.

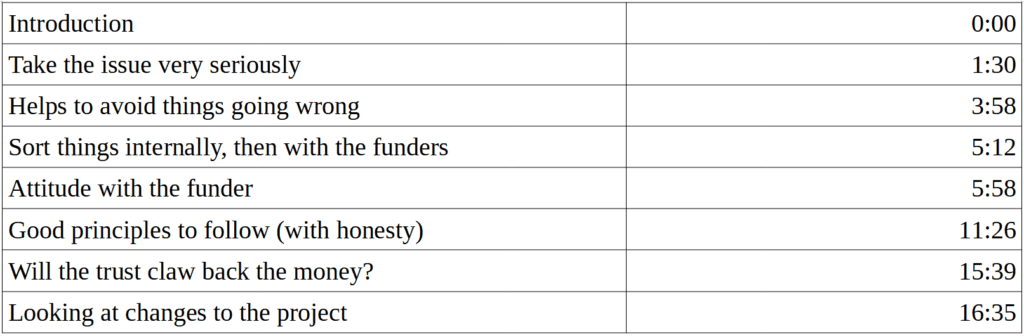

Grants officer Edgar Villanueva raises, ‘The risk of talking honestly about what’s going well and what isn’t, which is of losing funding.’ At the same time, we have obligations under the Fundraising Code of Practice and common decency to not deceive our grants officers. The following video gives ideas about how to do whatever you can to preserve things – and even to use the problem to actually strengthen the relationship.

This video is very focused on the narrow issue of what to do with the funder. However, the big picture is that you’ll often need to have worked very hard on problem solving (a sub-menu on the Trusts Team menu) and to have worked with Services to sort things out (the Work with Services sub-menu on the Internal menu). What you say to the funder often mainly comes after all that work has been completed.

Since doing that video, I’ve identified another useful little tool to crack open the issue of explaining why it’s not your fault, if it isn’t. You can do a Why Diagram (described in the Problem Solving video, or online) focusing on the project’s dependencies.

To take a recent example: we had a project that we’d delivered very well in part and spent all the donor’s money on, but we hadn’t delivered some other work that was in the overall project description and wanted to explain that to the funder. The un-delivered work was some early intervention casework.

So, to break down the causes (secondary causes are further to the right, primary ones further left):

Ability to deliver casework

Clearly some of these arguments are neater things to say than others. If we kept digging, there’s probably more again that we could have said.